The Economy of Generosity

At the Study & Practice class last night, I explained that I set a registration fee for the class ($20), which is a fee-for-service arrangement that participates in our “normal” market economy (in which I collect a fee to cover the costs that I have to pay).

But I teach the class under an entirely different arrangement. It’s what Buddhist call the Practice of Dana, which I think of as an Economy of Generosity: I offer the teachings freely — as an expression of my love and appreciation for these teachings and for those who have taught me — and in doing so, I provide an opportunity for the people who are taking my class to participate in this same Economy of Generosity. By which I mean the opportunity for them to give freely (to me financially, yes, but in other ways too, such as to the class by participating whole-heartedly).

Or not.

Either way is OK with me. (That’s what makes it an Economy of Generosity.)

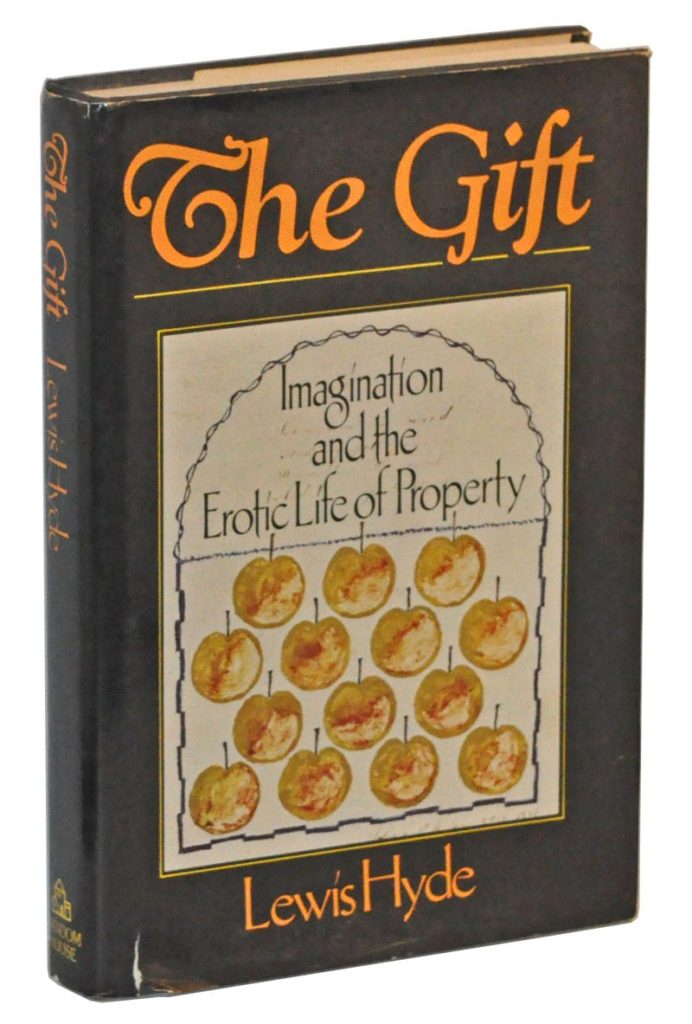

After the class, I got to talking with a friend about this idea of giving and receiving, and I recalled a book I read when I was in college that had a tremendous impact on me. The book is The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, by Lewis Hyde. (I had mis-remembered the title as: The Erotic Life of Generosity, which maybe says something about why it had such an impact on my understanding of generosity!)

My friend also mentioned a book about Art and Generosity, which had a big impact on him, and after looking around on Google, I think maybe this is the same book! It’s now called The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, and apparently it’s recently been re-published in a special twenty-fifth anniversary edition.

Here’s a sample from the Introduction (original 1983 edition), which now that I’m reading it with “Buddhist eyes,” has a whole other level of meaning:

“There are several distinct senses of ‘gift’ that lie behind these ideas, but common to each of them is the notion that a gift is a thing we do not get by our own efforts. We cannot buy it; we cannot acquire it through an act of will. It is bestowed upon us. Thus we rightly speak of ‘talent’ as a ‘gift,’ for although a talent can be perfected through an effort of will, no effort in the world can cause its initial appearance. Mozart, composing on the harpsichord at the age of four, had a gift.

“We also rightly speak of intuition or inspiration [and I would add: insight] as a gift. As the artist works [as the meditator practices], some portion of his creation [her insight] is bestowed upon him [her]. An idea pops into his head, a tune begins to play, a phrase comes to mind, a color falls in place on the canvas. Usually, in fact, the artist does not find himself engaged or exhilarated by the work, nor does it seem authentic, until this gratuitous element has appeared, so that along with any true creation comes the uncanny sense that ‘I,’ the artist, did not make the work. ‘Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me,’ says D. H. Lawrence.” [The Buddhist teaching of Not-self!]

The first chapter of The Gift continues exploring the nature of gifts and giving:

“…a cardinal property of the gift: whatever we have been given is supposed to be given away again, not kept. Or, if it is kept, something of similar value should move on in its stead, the way a billiard ball may stop when it sends another scurrying across the felt, its momentum transferred. You may keep your Christmas present, but it ceases to be a gift in the true sense unless you have given something else away. As it is passed along, the gift may be given back to the original donor, but this is not essential. In fact, it is better if the gift is not returned but is given instead to some new, third party. The essential is this: the gift must always move. There are other forms of property that stand still, that mark boundary or resist momentum, but the gift keeps going.”