Beneath the Surface Glitter

The KM Book Study group meets tonight to continue our discussion of In the Buddha’s Words, by Bhikkhu Bodhi. We’re on Chapter 6: Deepening One’s Perspective on the World.

Here’s an excerpt:

“To follow the Buddha in the direction he wants to lead us, we have to learn to see beneath the surface glitter of pleasure, position, and power that usually enthralls us, and at the same time, to learn to see through the deceptive distortions of perception, thought, and views that habitually cloak our vision.

“Ordinarily, we represent things to ourselves through the refractory prism of subjective biases. These biases are shaped by our craving and attachments, which they in turn reinforce. We see things that we want to see; we blot out things that threaten or disturb us, that shake our complacency, that throw into question our comforting assumptions.

To undo this process involves a commitment to truth that is often unsettling, but in the long run proves exhilarating and liberating.”

***

Let’s dive in!

At the Threshold

From In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History, by Mitch Landrieu, which my CDL “White Awake” group will be discussing next month:

From In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History, by Mitch Landrieu, which my CDL “White Awake” group will be discussing next month:

“Unlike the cursing anonymous voice on a telephone, or the menacing face, or the billy club that split John Lewis’s head in Selma, Alabama at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, implicit bias is hard to see; implicit bias is a silent snake that slinks around in ways we don’t notice.

“Questions gather at the threshold of transformative awareness. Whom do we sit with at lunch? Who are the kids we invite to our children’s parties? Or look at for honors programs at school? Who do we think of as smart, with good moral fiber, God-loving and patriotic? To whom do we give the benefit of the doubt, and why? Who are the people we condemn most quickly?

“As questions multiply about the consequences of race, it forces you to look in the mirror and see yourself as you really are, not who you’ve been told you are, not who society has made you to be, and not the image you want others to perceive.

“That’s when you start noticing things about yourself you never thought about before. The sight is not always pretty.”

Deliberately More Colloquial

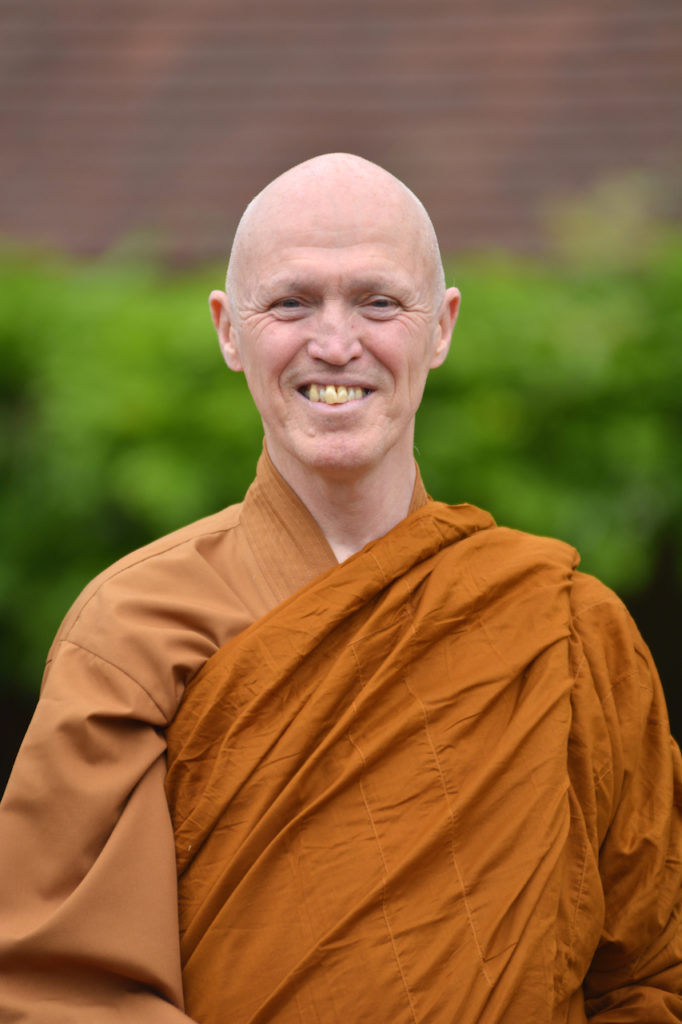

I’d like to share this wonderfully straight-forward translation of the Four Noble Truths from Turning the Wheel of Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching, by Ajahn Sucitto (pictured here).

I’d like to share this wonderfully straight-forward translation of the Four Noble Truths from Turning the Wheel of Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching, by Ajahn Sucitto (pictured here).

“There is a noble truth with regard to suffering. Birth is difficult; aging is hard; dying is painful. Sorrow, grieving, pain, anguish, and despair are all painful. Being stuck with what you don’t like is stressful; being separated from what you do like is stressful; not getting what you want is stressful. In brief, the five aggregates that are affected by clinging bring no satisfaction.

“There is a noble truth concerning the arising of suffering: it arises with craving, a thirst for more that’s bound up with relish and passion and is always running here and there. That is: thirst for sense-input, thirst to be something, thirst to not be something.

“There is a noble truth about the cessation of suffering. It is the complete fading away and cessation of this craving; its abandonment and relinquishment; getting free from and being independent of it.

“There is a noble truth of the way leading to the cessation of suffering. It is the noble eightfold path: namely, right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.”

***

In the introduction, Sucitto explains: “…since the teaching was given so long ago in a culture different from our own, its wording and allusions can cause us modern readers to stumble. For starters, it’s written in the Pali language, which is an amalgam of various ancient, vernacular Indian dialects. This language of the text is similar to Sanskrit, but is deliberately more colloquial.

“This is because the Buddha chose to teach in the spoken dialects of ordinary people in order to get his message across more readily–not that this helps the modern Westerner. Sanskrit was the literary language, reserved for the upper caste, so by using ordinary language, the Buddha was making the point that his teaching wasn’t philosophical or only for the learned. Instead, it is supposed to reach ordinary people, be matter-of-fact, and accessible.”

***

I think Ajahn Sucitto’s translation goes a long way toward doing just that.

Resist Ugliness in the World….

I’d like to recommend another wonderful new book: The State of Mind Called Beautiful, by Sayadaw U Pandita, translated by Ven. Vivekananda, and edited by Kate (Lila) Wheeler (who just happens to be my mentor!).

I’d like to recommend another wonderful new book: The State of Mind Called Beautiful, by Sayadaw U Pandita, translated by Ven. Vivekananda, and edited by Kate (Lila) Wheeler (who just happens to be my mentor!).

Here’s an excerpt from Lila/Kate’s preface:

“The talks in this book were given at a one-month retreat in May 2003 inaugurating the Forest Refuge, the long-term retreat facility at Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts…

“The panorama begins with the fundamental teachings. Dhamma, the truth, is what we should do; Vinaya, the discipline, is what we should stop doing. Between these two, our practice is like planting flowers and pulling up weeds.

“It its necessary to do practices that strengthen the mind and heal societies and families, because violence, war, and instability mark our current days. These practices are called the four guardian meditations. They uplift and protect us, and even long-term meditators are asked to practice them.

“But inner actions like mediation are not enough. There must be outer, compassionate activity–with no compromise of ethics. The Earth, he said, appears to be in the control of people who ‘resemble demons more than human beings.’

“Leaders who attempt to control these inhuman beings often sink to the same level themselves. We must resist this, he said. ‘Compassion, he observed, ‘says what needs to be said. And wisdom doesn’t fear the consequences.’

“At the time, his country was subject to a brutal dictatorship, and Sayadaw-gyi publicly supported democratic reforms at great personal risk to himself.

“Next he drilled deep into the fundamental mechanics of how a mind is healed by Dhamma. One of the core teachings of The State of Mind Called Beautiful is the exposition of how and why the Noble Eightfold Path is present in every moment of mindfulness. He also systematizes and concretizes the relationship between morality, concentration, and wisdom in ways that any psychoanalyst would admire.

“Restraint suppresses the physical acting out of impulses. Then outer life is calm, but the tormenting impulses are deeply embedded and likely to remain. Concentration training can divert the mind away from its obsessions. Finally, with sufficient clarity of mind, direct awareness can penetrate to the inherent lack of substance. This is how intuitive wisdom develops and dissolves the pain in the mind.

“‘The defilements are disgusting, dreadful, fearsome, and frightening,’ he thunders.

“Look around at the world. Ask yourself if this sounds right….

“The skills and clarity Sayadaw-gyi taught are indispensable these days, when the Buddha’s starkest teachings about the dangers of samsara are beginning to ring louder than ever before in our lifetime.

“With this in mind, we offer you The State of Mind Called Beautiful.“

Lost in Translation

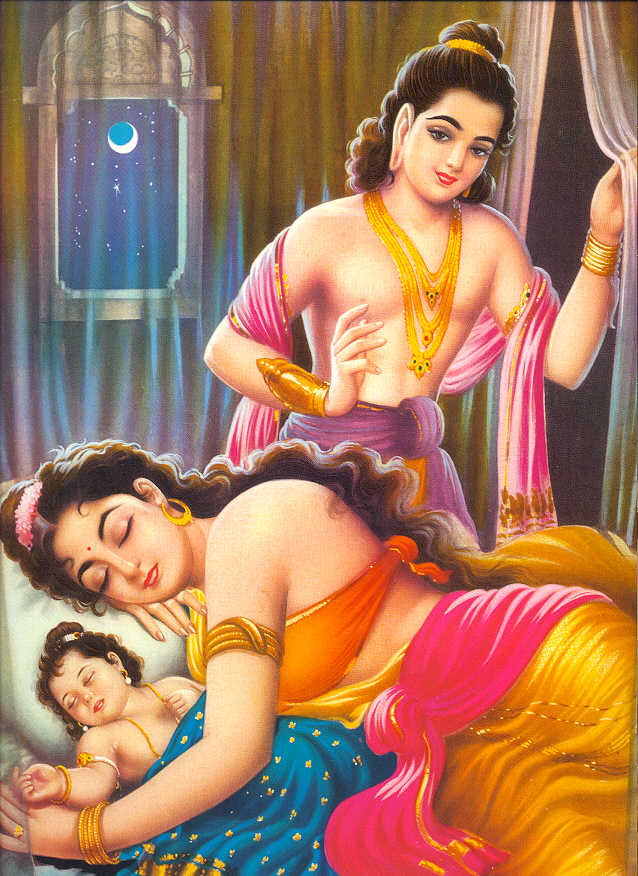

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

But now I’ve just run across this footnote in Turning the Wheel of the Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching, by Ajahn Sucitto:

“Many fables that present the life of the Buddha tell of his marriage and sudden nocturnal departure in a highly dramatic way that was designed to emphasize the great renunciation of the young seeker. Most of us these days would view nocturnal departures as anything but renunciation, so unfortunately this legend has cause the Buddha to be seen more as a jerk than one who negotiated his way out of the jam that his parents had put him in.”

Ah. That does put things is a bit of a different light.

Here’s the text that the footnote refers to:

“…When was he born? Traditions vary, placing his birth date anywhere between 573 B.C.E. and 483 B.C.E. Modern research suggests 480 B.C.E.

“What is more commonly agreed upon is that he was born as the son and heir of Suddhodana, an elected chief of the Sakyan republic. This republic occupied a fragment of southern Nepal on the Indian border, and probably extended into what is now the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The son was named Siddhattha Gotama (Skt.: Siddhartha Gotama).

“Although a lot is made in subsequent legends of his early life, the Buddha only referred to it a few times. The Sakyan republic was not a grand kingdom; it was a vassal state of another small kingdom occupying the northeast of Uttar Pradesh. So he was a nobleman in a small republic.

“In his teens he was bound into an arranged marriage for dynastic reasons. This marriage was anything but a love affair–it’s unlikely that the couple had even laid eyes on each other before the wedding. However that’s the way it was done in those days; the important thing was to bring forth a son as a guarantor for the future of the family. After thirteen years, the couple managed to do that, and so, after some protracted and painful negotiations, Siddharttha got permission from his family to take leave and pursue a spiritual quest as one ‘gone forth.’

“Siddhattha’s departure meant that he gave up everything. He relinquished inheritance, statehood, livelihood, family network, friends, and caste–all the elements that in Indian society gave him a place in the cosmos–which included not only this world and life, but also a future birth.

“So with ‘going forth’ he had put aside his ascribed place in the cosmic order to find a new one for himself. Relinquishment made life starkly simple–a ‘gone forth’ person had to survive on what he or she could glean, and put everything else aside to focus on developing his or her mind, soul, or spirit. Whatever you think of his domestic policy, you can’t fault Siddhartha in terms of putting his life on the line.

“He wasn’t entirely alone in this–there was a whole movement of samanas (religious seekers) doing the same kind of thing–sometimes following a particular teacher and sometimes forming groups and adhering to an ethical code of harmlessness, celibacy, truthfulness, and renunciation.

“To be a true ‘gone-forth one,’ however, the essential factor was to wander free from the ties and comforts of home life. This was life with the veils and wrapping pulled off. It was life among wild animals, thieves, and outlaws–life lived on the hard earth at the roots of trees; seeking alms-food from villages; and looking for something to wear, often pulling rags off the corpses whose jackal-chewed remains littered the charnel grounds.

“It was life held like a brief candle-flame in the vast stormy night of sickness, danger, and death. Only a few ventured into this way fo life, some of dubious sanity, some quiet saintly, but all were held in a mixture of fear and awe by the ordinary folk of town, clan, and family.”

On Doing What Needed to Be Done

Last summer I was thrilled and inspired by New Orlean’s Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech given just before the Confederate statues were taken down. (I posted an excerpt here.)

Last summer I was thrilled and inspired by New Orlean’s Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech given just before the Confederate statues were taken down. (I posted an excerpt here.)

And now I’m even more thrilled that Mayor Landrieu has written a book about these events. It’s titled In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History.

Wow.

Here’s an excerpt from the prologue:

Here I was, mayor of a major American city in the midst of a building boom like no other, filled with million-dollar construction jobs, and I couldn’t find anyone in town who would rent me a crane. Are you kidding me?!

…The people of the city of New Orleans, through their elected government, had made the decision to take down four Confederate monuments, and it wasn’t sitting well with some of the powerful business interest in the state. When I put out a bid for contractors to take them down, a few responded. But they were immediately attacked on social media, got threatening calls at work and at home, and were, in general, harassed. This kind of thing normally never happens. Afraid, most naturally backed away. One contractor stayed with us. And then his car was firebombed. From that moment on, I couldn’t find anyone willing to take the statues down.

I tried aggressive, personal appeals. I did whatever I could. I personally drove around the city and took pictures of the countless cranes and crane companies working on dozens of active construction projects across New Orleans. My staff called every construction company and every project foreman. We were blacklisted. Opponents sent a strong message that any company that dared step forward to help the city would pay a price economically and even personally.

Can you image? In the second decade of the twenty-first century, tactics as old as burning crosses or social exclusion, just dressed up a little bit, were being used to stop what is now an official act, authorized by the government in the legislature, judicial, and executive branches.

This is the very definition of institutionalized racism. You may have the law on your side, but if someone else controls the money, the machines, or the hardware you need to make your new law work, you are screwed. I learned more and more that this is exactly what has happened to African Americans over the last three centuries. This is the difference between de jure and de facto discrimination in today’s world. You can finally win legally, but still be completely unable to get the job done. The picture painted by African Americans of institutional racism is real and was acting itself out on the streets fo New Orleans during this process in real time.

In the end, we got the crane. Even then, opponents at one point had found their way to one of our machines and poured sand in the gas tank. Other protesters flew drones at the contractors to thwart their work. But we kept plodding through. We were successful, but only because we took extraordinary security measures to safeguard equipment and workers, and we agreed to conceal their identities. It shouldn’t have to be that way….

This has been a long and personal story for me. I hope that this book meets each reader wherever they are in their own journey on race, and that my own story gives each of them the courage to continue to move forward. I hope that this book helps create hope for a limitless future. Now is the time to actually make this city and country the way they always should have been. Now is the time for choosing our path forward.

***

Amen!

Reading Outside the (Color) Line

One of the (many) things that has changed in my life since participating in the Waking Up to Whiteness program (which I posted about here) is that I’ve started to notice how much of what I read is written by white people, about white people. Which is understandable — since I’m white. But so limiting!

Now I’m really making a conscious effort to break out of that pattern. To which end: I just started reading Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

I picked it because the New York Times recently listed it as one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

(Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday, which I just finished reading and posted about here, was also listed. Click here for the compete Times listing.)

In the past, I probably wouldn’t have even noticed this novel. Which would have been a shame, because it’s TERRIFIC!!!

Here’s a sample from the first few pages:

“The man standing closest to her was eating an ice cream cone; she had always found it a little irresponsible, the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men, especially the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men in public. He turned to her and said, ‘About time,’ when the train finally creaked in, with the familiarity strangers adopt with each other after sharing in the disappointment of a public service. She smiled at him. The graying hair on the back of his head was swept forward, a comical arrangement to disguise his bald spot. He had to be an academic, but not in the humanities or he would be more self-conscious. A firm science like chemistry, maybe. Before, she would have said, ‘I know,’ that peculiar American expression that professed agreement rather than knowledge, and then she would have started a conversation with him, to see if he would say something she could use in her blog.

“People were flattered to be asked about themselves and if she said nothing after they spoke, it made them say more. They were conditioned to fill silences. If they asked what she did, she would say vaguely, ‘I write a life-style blog,’ because saying, ‘I write an anonymous blog called Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black’ would make them uncomfortable.

“She had said it, though, a few times. Once to a dreadlocked white man who sat next to her on the train, his hair like old twine ropes that ended in a blond fuzz, his tattered shirt worn with enough piety to convince her that he was a social warrior and might make a good guest blogger. ‘Race is totally overhyped these days, black people need to get over themselves, it’s all about class now, the haves and the have-nots,’ he told her evenly, and she used it as the opening sentence of a post titled ‘Not All Dreadlocked White American Guys Are Down.'”

The More You Learn…

I just finished reading Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday, and now all I want to do is to read it all over again.

I won’t attempt to write a review. The New York Times has a wonderful one here. So does NPR, here. And The Atlantic, here. Instead, I’ll just say that the experience of reading this book has taught me way more than I ever thought possible about a situation that I thought I already knew way too much about, and about a totally different situation that I knew I knew nothing about, but didn’t know just how much of this “nothing” I knew nothing about.

*** The book is written in three sections. The first is titled: Folly. It begins like this:

Alice was beginning to get very tired of all this sitting by herself with nothing to do: every so often she tried again to read the book in her lap, but it was made up almost exclusively of long paragraphs, and no quotation marks whatsoever, and what is the point of a book, thought Alice, that does not have any quotation marks?

She was considering (somewhat foolishly, for she was not very good at finishing things) whether one day she might even write a book herself, when a man with pewter-colored curls and an ice-cream cone from the Mister Softee on the corner sat down beside her.

“What are you reading?”

Alice showed him.

“Is that the one with the watermelons?”

Alice had not yet read anything about watermelons, but she nodded anyway.

“What else do you read?”

“Oh, old stuff, mostly.”

They sat without speaking for a while, the man eating his ice cream and Alice pretending to read her book.

Two joggers in a row gave them a second glance as they passed. Alice knew who he was–she’d known the moment he sat down, turning her cheeks watermelon pink–but in her astonishment she could only continue staring, like a studious little garden gnome, at the impassable pages that lay open in her lap. They might as well have been made of concrete.

“So,” said the man, rising. “What’s your name?”

“Alice.”

“Who likes old stuff. See you around.”

*** The second section is titled: Madness. It begins like this:

Where are you coming from?

Los Angeles.

Traveling alone?

Yes.

Purpose of your trip?

To see my brother.

Your brother is British?

No.

Whose address is this then?

Alastair Blunt’s.

Alastair Blunt is British?

Yes.

And how long do you plan to stay in the UK?

Until Sunday morning.

What will you be doing here?

Seeing friends.

For only two nights?

Yes.

And then?

I fly to Istanbul.

Your brother lives in Istanbul?

No.

Where does he live?

In Iraq.

And you’re going to visit him in Iraq?

Yes.

*** The third section is titled: Ezra Blazer’s Desert Island Discs. It begins like this:

Interviewer: My castaway this week is a writer. A clever boy originally from the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he graduated from Allegheny College swiftly into the pages of “Playboy,” “The New Yorker,” and “The Paris Review,” where his short stored about postwar working-class Americans earned him a reputation as a fiercely candid and unconventional talent. By the time he was twenty-nine, he had published this first novel, “Nine Mile Run,” which won him the first of three National Book Awards; since then he’s published twenty more books, and received dozens more awards, including the Pen/Faulkner Award, the Gold Medal in Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, two Pulitzer Prizes, the National Medal of Arts, and just this past December–“for his exuberant ingenuity and exquisite powers of ventriloquism, which with irony and compassion evince the extraordinary heterogeneity of modern American life”–literature’s most coveted honor: the Nobel Prize.

***

Somewhere in the middle of the first section, I underlined this: The more you learn, thought Alice, the more you realize how little you know.

Right.

I Find Myself, Again, Always….

One more passage from Calvino’s Invisible Cities, before I enter the silence tomorrow at the Forest Refuge:

Kublai: I do not know when you have had time to visit all the countries you describe to me. It seems to me you have never moved from this garden.

Polo: Everything I see and do assumes meaning in a mental space where the same calm reigns as here, the same penumbra, the same silence streaked by the rustling of leaves. At the moment when I concentrate and reflect, I find myself again, always, in this garden, at this hour of the evening, in your august presence, though I continue, without a moment’s pause, moving up a river green with crocodiles or counting the barrels of salted fish being lowered into the hold.

Kublai: I, too, am not sure I am here, strolling among the porphyry fountains, listening to the splashing echo, and not riding, caked with sweat and blood, at the head of my army, conquering the lands you will have to describe, or cutting off the fingers of the attackers scaling the walls of a besieged fortress.

Polo: Perhaps this garden exists only in the shadow of our lowered eyelids, and we have never stopped: you, from raising dust on the fields of battle; and I, from bargaining for sacks of pepper in distant bazaars. But each time we half-close our eyes, in the midst of the din and the throng, we are allowed to withdraw here, dressed in silk kimonos, to ponder what we are seeing and living, to draw conclusions, to contemplate from the distance.

Kublai: Perhaps this dialogue of ours is taking place between two beggars nicknamed Kublai Khan and Marco Polo; as they sift through a rubbish heap, piling up rusted flotsam, scraps of cloth, wastepaper, while drunk on the few sips of bad wine, they see all the treasure of the East shine around them.

Polo: Perhaps all that is left of the world is a wasteland covered with rubbish heaps, and the hanging gardens of the Great Khan’s palace. It is our eyelids that separate them, but we cannot know which is inside and which is outside.

***

Friends: I will return from retreat on January 31 and hope to post again during the first week of February.

Till then, may you all be safe, healthy, and happy!

Till the Period of Sojourn is Over

Note: This will be my last post until I return from 5 weeks of silent retreat at the Forest Refuge in Barre, Mass.

Note: This will be my last post until I return from 5 weeks of silent retreat at the Forest Refuge in Barre, Mass.

To accompany you as you embark on your own expedition into 2018, I offer this passage from Invisible Cities, by Italo Calvino:

Thin Cities 4

The city of Sophronia is made up of two half-cities. In one there is the great roller coaster with its steep humps, the carousel with its chain spokes, the Ferris wheel of spinning cages, the death-ride with crouching motorcyclists, the big top with the clump of trapezes hanging in the middle. The other half-city is of stone and marble and cement, with the bank, the factories, the palaces, the slaughterhouse, the school, and all the rest.

One of the half-cities is permanent, the other temporary, and when the period of sojourn is over, they uproot it, dismantle it, and take it off, transplanting it to the vacant lots of another half-city.

And so every year the day comes when the workmen remove the marble pediments, lower the stone walls, the cement pylons, take down the Ministry, the monument, the docks, the petroleum refinery, the hospital, load them on trailers, to follow from stand to stand their annual itinerary.

Here remains the half-Sophronia of the shooting-galleries and the carousels, the shout suspended from the cart of the headlong roller coaster, and it beings to count the months, the days it must wait before the caravan returns and a complete life can begin again.