We’re Not Having an Experience…

“We’re not having an experience, we are an experience. An experience that’s changing, that’s affected.”

— Ajahn Sucitto during a guided meditation on Disengaged Awareness. “Allowing content to arise and manifest generates spaciousness and eases the sense of self.” Click here to listen.

All the Elsewheres

Atmospherics

by Susan Hutton

Sometimes on a late clear night you can pull that station from Denver

or Boston out of the dark.

All the elsewheres alter here, as what you remember

changes what you think.

Not spider nor plum nor pebble possess any of the names we give them.

A kite tugging on its string gives you a sense of what’s up there,

though it is translated, and by a string.

Out there, in the dark, the true thing.

In The Very Same Place

FULL MOON REFLECTION from the Forest Sangha

Fearlessness

Whoever has cut all that tethers

and found fearlessness,

who is beyond attachments

and defilements,

I recognize as a great being.

— Dhammapada v. 397

“To be able to abide in the state of fearlessness sounds attractive indeed, but how might we reach such an abiding? Fearlessness is to be found in the very same place as that in which we feel fear.

“We do not need others to stop behaving the way that they do; nor do we need to go some place else. We do, however, need to look more deeply into the reality of the fear that we are already experiencing, and to do so can be very frightening. The temptation to turn away from that which frightens us can be strong. This is why the Buddha wanted us to develop our spiritual faculties: mindfulness, sense restraint, and wise reflection.

“When our heart is buoyed up with the wholesome sense of self confidence which arises when the spiritual faculties are well-developed, we won’t be so intimidated by fear; instead we will be interested in what fear has to teach us.”

Compassion Incantation

I’m thinking of someone who’s going through a difficult time right now, so I’d like to offer these phrases, which Phillip Moffitt uses in his Compassion Practice:

I can feel your suffering.

May your suffering cease.

May the light of love and understanding penetrate the darkness of this loss and grief.

May your suffering cease.

May your suffering cease.

***

Phillip suggests being as specific as possible, so instead of “loss and grief,” which are appropriate in the situation I’m thinking of, one could use “pain and despair,” or “fear and uncertainty,” or whatever else feels right.

Listen to Phillip speak about these phrases and how to work with them in his talk: Surrender, Collapse, Conquer, and Compassion, part 2.

Understandable Results of Unbalanced Energy

My “Headphone Retreat” continues. Last night I listened to Ajahn Sucitto’s talk on Intention, which concludes with a wonderful explanation of the Five Hindrances as “understandable results of unbalanced or depleted energy” (and therefore to be seen as “less of a sin and more of a problem that can be amended.”)

Sucitto says, “The body and mind are in sympathy and they are co-dependent. So at this level, the way you inflect your mind effects your body energy. If you approach your body from a controlling attitude, then your body will start to become rigid on a physiological level. If you approach it from an acceptance place, it becomes softer, more relaxed.

“So what is the proper relationship? To not be dominating, but at the same time, be present. This is a very beautiful skill to learn. And naturally the success rate is not all that great. [laughs] But if you are getting a 1 or 2 out of 10, this is definitely progress. Because every time you touch that, faith arises.

“There are definitely big benefits in the sense of self dropping away, the obsessiveness or the moodiness dropping away. Because in the relational sense, when that is harmonious, the quality of harmony becomes the atmosphere. And the disharmonious qualities drop away.

“Then one feels settled, composed. This is called samadhi. It’s harmony — unification of body and mind. That’s when the mental energy and the body energy are in synch. They’re in synergy. So what occurs is there’s an overall sense of harmony, unification, and settledness.

“And that has not arisen really from me trying to get things calmed down. (Unless it’s done in a very careful way.) Certainly the inclination is: Let’s just take things easier; there’s no pushing; no pressure; just stay present. The inflection of an intentionality is something that no matter how many words I put around it, you will have to find it for yourself. And it may have different words for you.

“But the result will be, definitely a cleaning of behavior on a subtle level. And that cleaning on a subtle level will definitely have effects on a more obvious relational level. One becomes less fearful or pushy. One becomes less flustered in the presence of phenomena that are not delightful or attractive. Because the energy itself builds up a certain strength.

“So as our bodily energy system becomes more strengthened and cleaned, then we’re able to be present with difficult phenomena without feeling highly impacted. It’s not that you don’t notice them, but you don’t feel shocked by them. Or tightened up. Or defensive.

“These are the effects that occur from the skill that comes with this kind of mode of practice. Because the body and the mind are not separable — they effect each other — then the negative effects of the defective behaviors of grasping and so forth…they are felt in the body and the mind.

“The first list of these defective behaviors we know so well — The Five Hindrances.

“Greed or sense desire:

“This is because the energy feels really flat and needs something to get it going. It’s hungry. It lacks vitality. So it’s got to have something to feed on, to get livened up with. Clearly, if one has vitality, this does not have to occur.

“Ill-will:

When we cannot cope with difficult feelings, we get hostile instead. Energy tightens up because it has no capacity to accommodate and discharge the difficult feeling. So instead it develops hostility towards it. Prickling and souring.

“Dullness:

“Because so much of the energy gets exported into distraction and outgoing tendencies, one’s ‘home base,’ one’s ‘reservoir,’ is rather low. One hasn’t got a rich supply of energy because so much of it goes out through the sense doors and in occupations. So there’s not much ‘at home.’ Therefore one’s dullness is a sort of indolence and a sluggishness.

“Restlessness:

“Because so much energy is expended in sense phenomena — which are diverse — the system is used to jumping from this to that, to this, to that, to this, to that. So that pattern gets established. Now if there’s a sense of something that’s unifying, that the citta [heat/mind] can go to… if there’s a unifying energy…. then it can settle into that. So restlessness can cease.

“Speculative doubt:

“This is when we are over-emphasizing the conceptual intelligence. This is what happens when the other intelligences are more limited. If our body intelligence isn’t very acute, and the heart intelligence is not so agile, then what happens is a lot of the intelligence goes into the mental faculty. Which means we are always searching for clarity and answers to things.

“But the mental faculty can’t provide it. It cannot provide the satisfaction that can only be really experienced in the heart. This is the state of doubt: ‘Is it this or that…’ ‘Should I do this or that…’ What’s being sought is the sense of: ‘Ah-hahhh.’ And that is a heart sense.

“If the heart intelligence has not been properly energized and brought to bear upon experience, then speculative doubt becomes potentially more apparent. Because we seek orientation in terms of thought. But thought cannot provide it. So there’s the sense of: ‘maybe this… or maybe that…’ Because we’re still looking for the clarity orientation that cannot arrive. It’s like walking on water. It can’t be done. So there’s the skidding effect of doubt. Confidence arises not from the intellect, but from realization of citta: ‘Ahh. This is this.’

“These hindrances have energetic effects, though very often in dharma instruction the approach is more from the psychological aspect — which is also true — but I feel that the psychological qualities that we attune to, this area of our intelligence, is so over-worked that it’s almost inflamed — with self-hood — and with blaming, and criticism, and guilt around these hindrances.

“So perhaps it would be easier to sense them as just understandable results of unbalanced or depleted energy. And then it becomes less a “sin” and more of a problem that can be amended. By accessing, steadying, smoothing, calming — forming a healthy relationship. And breathing is certainly an excellent object for that because it will give you a lot back.

“It will give you a lot back — if you approach it in the right way.”

***

The excerpt above begins at about the 45 minute mark. Click here to listen to this talk in its entirety.

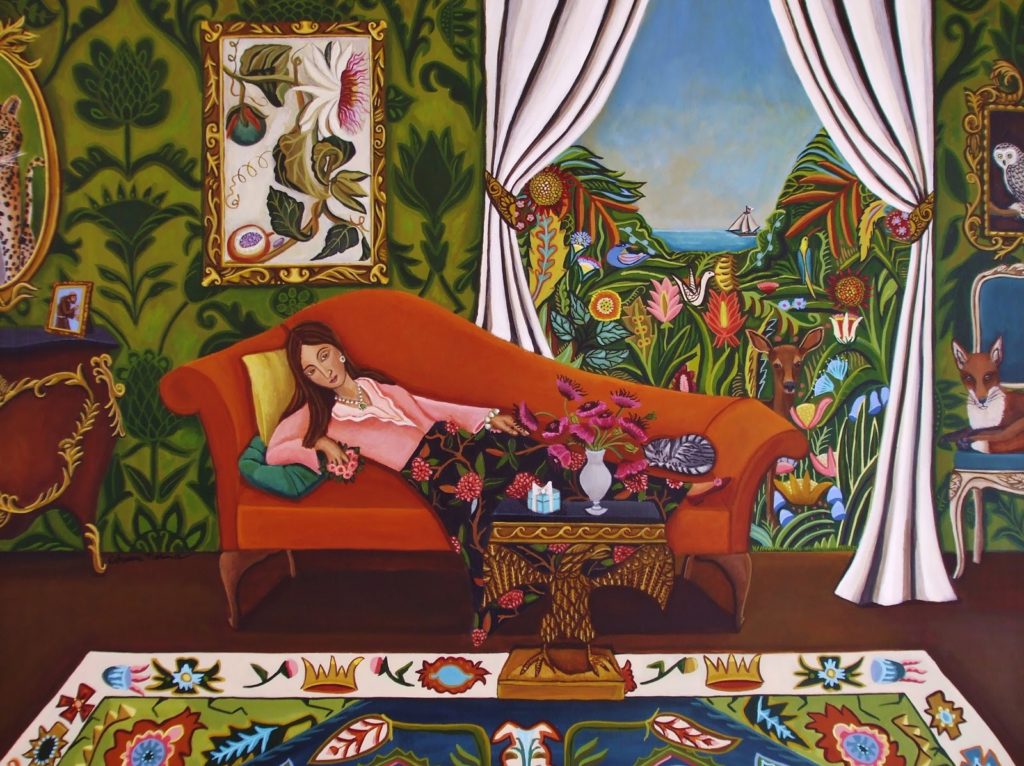

This One (Other) Thing

For those who might wonder if maybe I don’t ever do anything other than meditate (and write blog posts), today I want to share with you a different kind of project, which I’m also immersed in. (Although it too is somewhat of a meditative undertaking!)

For those who might wonder if maybe I don’t ever do anything other than meditate (and write blog posts), today I want to share with you a different kind of project, which I’m also immersed in. (Although it too is somewhat of a meditative undertaking!)

I’ve joined The Sketchbook Project — a world-wide community of over 70,000 artists designed to “nurture community-supported art projects that harness the power of the virtual world to share inspiration in the real world.”

So now I’m working on filling up one of the Project’s standard-issue sketchbooks with drawings that resonate for me on the theme: This One Thing.

And when it’s finished (it’s due Feb 15), it’ll become one of more than 40,000 on display — and available for check-out — at the Brooklyn Art Library!

The photo above is the first page of the sketchbook.

Here’s another page, about half-way through the book:

Here’s the page I’m working on now:

There are still four more pages to go. Stay tuned!

Head-Phone Retreat!

I discovered last night that talks from Ajahn Sucitto’s month-long retreat — going on right now at the Forest Refuge — are starting to be posted on Dharma Seed.

I discovered last night that talks from Ajahn Sucitto’s month-long retreat — going on right now at the Forest Refuge — are starting to be posted on Dharma Seed.

I had tried to attend this retreat, but my name didn’t get drawn. (Admission was by lottery.) The same thing happened to me when I tried to attend this retreat last year…and the year before that, and the year before that, and the year before THAT.

So I decided it’s time for a new plan.

Instead of trying to win the Sucitto retreat lottery, I’m just going to meditate at home — BUT I’M STILL GOING TO SIT HIS RETREAT — because I can listen to the talks on-line.

I’ll call it a head-phone retreat!!!

So I started it last night by listening to this very sweet little opening talk (just 14 minutes long), in which Sucitto explains the practice of alms giving (the ritual offering of a meal to monastics) — which I had never really given much thought to until the first time I attended a retreat where a monk was present, and then was so moved by the care and respect with which it was done, that I found myself welling up with tears.

Here’s what Sucitto says about this in the first talk of the retreat:

“The first thing that’s going to involve us monastics is the alms giving. This is a sign of the reciprocity in which everybody contributes, everybody participates and shares, in a kind of quiet and restrained and careful way. And so it establishes a relationship with an essential quality that has a certain special focusing, even sacred nature, to it.

“Because when we relate to each other, then we have to come out of our self a little bit — meet the other in that uncertain place. And that’s where these valuable qualities of goodwill, self-respect, respect-for-other, and meaning, can occur.

“So the alms giving is not just having a meal. Essentially, the principle is, that the sammanas — “gone-forth people” we call monastics — make themselves available to receive what is offered. So the principle of our mendicant life is we never ask for anything, it’s that we just make ourselves available. That’s the principle of it.

“For those who offer it’s not like: What would you want? What would you like? But: May I offer? And then whatever is offered, we receive it. So that allows a certain kind of openness, and the other people come in as they will. They don’t have to offer anything. If not, well, then OK, maybe next time…

“Essentially, what is most highly regarded is the quality of the offering — the offering gesture — and the smoothness or the clarity, the caring quality that’s imbued in that, rather than the actual nature of the material object.

“As gone-forth people, we place matters of the heart above matters of material form. These matters of the heart are: generosity, sharing, respect, and invitation and offering, rather than demand and obey…”

***

Sucitto then goes on to a few other items, concluding with this lovely bit of instructions for settling in:

“While you’re finding your way into the retreat, let’s make the effort to draw a circle around your life. Keeping it within this particular physical situation. So you can walk around the whole of the retreat facility — that’s including the woodlands — but let’s keep in this particular property, so you’ve got some sense of a boundary.

“And bring all your concerns within that. How you act, how you walk, how you relate to the earth, how you relate to other people, how you relate to your body, and how you relate to the sacred — to these four compass points.

“The earth, nature, how you feel connected to that — you’re in that — a sense of respect and openness to that.

“To your own body — and here I will offer daily qigong to support you in that.

“How you relate to others — the precepts and the whole sense of acting as a group, which is part of that.

“And of course, how you relate to the sacred — your own values, your own virtues, both the moral virtues and the virtues in terms of parami — how you lift them up, how you respect them, how you respect them in others, how you venerate them in these symbolic ways using the shrine — so that’s the one that covers all of it. Everything should be held in that particular domain. So the earth, your body, other people, and the sacred. These are four compass points…”

***

There’s more to this talk. Click here to listen. (Maybe even try a head-phone retreat of your own!)

The Familiar is Not the Thing It Reminds Of

Red Berries

Red Berries

by Jane Hirshfield

Again the pyrocanthus berries redden in rain,

as if return were return.

It is not.

The familiar is not the thing it reminds of.

Today’s yes is different from yesterday’s yes.

Even no’s adamance alters.

From painting to painting,

century to century,

the tipped-over copper pot spills out different light;

the cut-open beeves,

their caged and muscled display,

are on one canvas radiant; obscene on another.

In the end it is simple enough–

The woman of this morning’s mirror

was a stranger

to the woman of last night’s;

the passionate dreams of the one who slept

flit empty and thin

from the one who awakens.

One woman washes her face,

another picks up the boar-bristled hairbrush,

a third steps out of her slippers.

That each will die in the same bed means nothing to them.

Our one breath follows another like spotted horses, no two alike.

Black manes and white manes, they gallop.

Piebald and skewbald, eyes flashing sorrow, they too will pass.

None of This is Spare Time

I’ve just run across a wonderfully titled book — No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters, a collection of essays by Ursula K. Le Guin — which I’m really trying to savor and take my time with (so to speak), but it’s such a delightful read that I’m sure I’ll come to the end way before I’m ready to. (Isn’t that always the way it is!)

Here’s a excerpt from the first essay in the collection:

“I got a questionnaire from Harvard for the sixtieth reunion of the Harvard graduating class of 1951. Of course my college was Radcliffe, which at that time was affiliated with but wasn’t considered to be Harvard, due to a difference in gender; but Harvard often overlooks such details from the lofty eminence where it can consider all sorts of things beneath its notice. Anyhow, the questionnaire is anonymous, therefore presumably gender-free; and it is interesting.

“The people who are expected to fill it out are, or would be, almost all in their eighties, and sixty years is time enough for all kinds of things to have happened to a bright-eyed young graduate….

“Question 14: ‘Are you living your secret desires?’… I finally didn’t check Yes, Somewhat, or No, but wrote in ‘I have none, my desires are flagrant.’

“But it was Question 18 that really got me down. ‘In your spare time, what do you do? (check all that apply).’ And the list begins: ‘Golf…’

“Seventh in the list of twenty-seven occupations, after ‘Racquet sports’ but before ‘Shopping,’ ‘TV,’ and ‘Bridge,’ comes ‘Creative activities (paint, write, photograph, etc.).’

“The key words are spare time. What do they mean?

“To a working person — supermarket checker, lawyer, highway crewman, housewife, cellist, computer repairer, teacher, waitress — spare time is the time not spent at your job or at otherwise keeping yourself alive, cooking, keeping clean, getting the car fixed, getting the kids to school. To people in the midst of life, spare time is free time, and valued as such.

“But to people in their eighties? What do retired people have but ‘spare’ time?

“I’m not exactly retired, because I never had a job to retire from. I still work, though not as hard as I did. I have always been and am proud to consider myself a working woman. But to the Questioners of Harvard my lifework has been a ‘creative activity,’ a hobby, something you do to fill up spare time. Perhaps if they knew I’d made a living out of it they’d move it to a more respectable category, but I rather doubt it.

“The question remains: When all the time you have is spare, is free, what to do you make of it?….

“The opposite of spare time is, I guess, occupied time. In my case I still don’t know what spare time is because all my time is occupied. It always has been and it is now. It’s occupied by living.

“An increasing part of living, at my age, is mere bodily maintenance, which is tiresome. But I cannot find anywhere in my life a time, or a kind of time, that is unoccupied.

“I am free, but my time is not.

“My time is fully and vitally occupied with sleep, with daydreaming, with doing business and writing friends and family on email, with reading, with writing poetry, with writing prose, with thinking, with forgetting, with embroidering, with cooking and eating a meal and cleaning up the kitchen, with consulting Virgil, with meeting friends, with talking with my husband, with going out to shop for groceries, with walking if I can walk and traveling if we are traveling, and sitting Vipassana sometimes, with watching a movie sometimes, with doing the Eight Precious Chinese exercises when I can, with lying down for an afternoon rest with a volume of Krazy Kat to read and my own slightly crazy cat occupying the region between my upper thighs and mid-calves, where he arranges himself and goes instantly and deeply to sleep.

“None of this is spare time. I can’t spare it. What is Harvard thinking of? I am going to be eighty-one next week. I have no time to spare.”

In Conversation

The most recent newsletter from the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies features an interview with Lila Kate Wheeler (one of my mentors) and Lama Rod Owens (co-author of Radical Dharma), who will be teaching a course together next month titled: Satipatthana in Dialogue with Suffering and Oppression. (I’ll be taking the course, so stay tuned!)

In the article, the interviewer asks about the idea of the course and what it will cover.

Lila responds:

Lila responds:

“We will practice the Satipatthana Sutta’s four frameworks – body, feeling tones, mind and liberation – as a lens to focus and look into the roots of suffering and relief. We will also represent contemporary notions of justice, like intersectionality…. As the course title indicates we’ll put the traditional teaching and contemporary understandings into conversation with each other.

“My late Burmese meditation master, Sayadaw U Pandita, told me at the end of an intensive loving kindness (metta) retreat: Metta cannot remain as an internal meditation, it is not strong enough to be called metta until it is completed with acts of body and speech. Mindfulness and wisdom, too, are incomplete until they are practiced in visible ways…”

Lama Rod adds:

Lama Rod adds:

“I believe that we are desperate in our community for dharma teaching to be linked directly to how dharma should be practiced in the world. It’s nice to learn metta but what does that have to do with being called a derogatory name on the subway? How can I call on goodness and positive goodwill when I am being threatened and especially when I am pissed off?

“I am always having to practice in this way because as a black man in American society, I have a higher risk of facing unjustified violence at even given time. I need my dharma practice to meet the anxiety of what it means to be embodied in this way in this given time.”

Lila continues:

“In our contemporary context, both retreat and daily life instructions teach mindfulness as an internal practice. Its benefits are mapped by MRI and singular brains are called outstanding or abnormally wonderful or just normally messy. This leads us to feel as if the individual were the context for examination.

“But a fuller practice of sati was originally and beautifully mapped out by the Buddha in the Satipatthana Sutta — the Discourse on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness — to include being aware of the bodies, feeling tones, minds and liberation internally, externally, and both. This is very rich territory that hasn’t been explored enough.”

Lama Rod explains:

“To practice an awareness of suffering we must be willing to turn our attention to the reality that what we enjoy comes at the cost of marginalizing others. This is an insight into the nature of interrelatedness as well as karma. Compassion or karuna reminds us of the suffering of others.

“I hope in this retreat that reminding can be further directed towards helping us understand that what we take for granted as being normal often comes at a cost to others. If we can learn to soften our hearts some then we can make more room in reducing as much harm as possible and begin to share more resources and make more room for others.

***

For the full interview, click here.