What the River Says

Ask Me

by William Stafford

Some time when the river is ice ask me

mistakes I have made. Ask me whether

what I have done is my life. Others

have come in their slow way into

my thought, and some have tried to help

or to hurt: ask me what difference

their strongest love or hate has made.

I will listen to what you say.

You and I can turn and look

at the silent river and wait. We know

the current is there, hidden; and there

are comings and goings from miles away

that hold the stillness exactly before us.

What the river says, that is what I say.

Lost in Translation

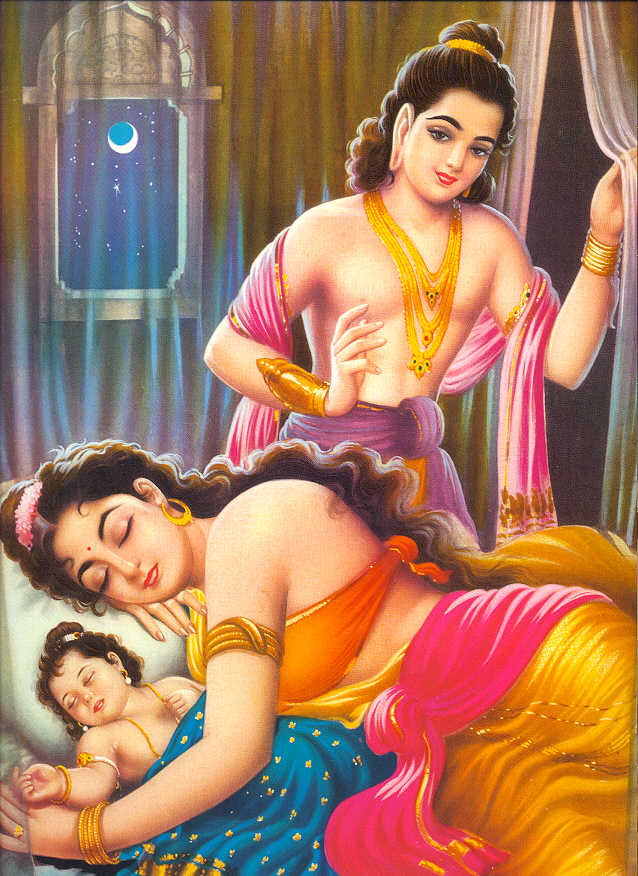

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

But now I’ve just run across this footnote in Turning the Wheel of the Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching, by Ajahn Sucitto:

“Many fables that present the life of the Buddha tell of his marriage and sudden nocturnal departure in a highly dramatic way that was designed to emphasize the great renunciation of the young seeker. Most of us these days would view nocturnal departures as anything but renunciation, so unfortunately this legend has cause the Buddha to be seen more as a jerk than one who negotiated his way out of the jam that his parents had put him in.”

Ah. That does put things is a bit of a different light.

Here’s the text that the footnote refers to:

“…When was he born? Traditions vary, placing his birth date anywhere between 573 B.C.E. and 483 B.C.E. Modern research suggests 480 B.C.E.

“What is more commonly agreed upon is that he was born as the son and heir of Suddhodana, an elected chief of the Sakyan republic. This republic occupied a fragment of southern Nepal on the Indian border, and probably extended into what is now the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The son was named Siddhattha Gotama (Skt.: Siddhartha Gotama).

“Although a lot is made in subsequent legends of his early life, the Buddha only referred to it a few times. The Sakyan republic was not a grand kingdom; it was a vassal state of another small kingdom occupying the northeast of Uttar Pradesh. So he was a nobleman in a small republic.

“In his teens he was bound into an arranged marriage for dynastic reasons. This marriage was anything but a love affair–it’s unlikely that the couple had even laid eyes on each other before the wedding. However that’s the way it was done in those days; the important thing was to bring forth a son as a guarantor for the future of the family. After thirteen years, the couple managed to do that, and so, after some protracted and painful negotiations, Siddharttha got permission from his family to take leave and pursue a spiritual quest as one ‘gone forth.’

“Siddhattha’s departure meant that he gave up everything. He relinquished inheritance, statehood, livelihood, family network, friends, and caste–all the elements that in Indian society gave him a place in the cosmos–which included not only this world and life, but also a future birth.

“So with ‘going forth’ he had put aside his ascribed place in the cosmic order to find a new one for himself. Relinquishment made life starkly simple–a ‘gone forth’ person had to survive on what he or she could glean, and put everything else aside to focus on developing his or her mind, soul, or spirit. Whatever you think of his domestic policy, you can’t fault Siddhartha in terms of putting his life on the line.

“He wasn’t entirely alone in this–there was a whole movement of samanas (religious seekers) doing the same kind of thing–sometimes following a particular teacher and sometimes forming groups and adhering to an ethical code of harmlessness, celibacy, truthfulness, and renunciation.

“To be a true ‘gone-forth one,’ however, the essential factor was to wander free from the ties and comforts of home life. This was life with the veils and wrapping pulled off. It was life among wild animals, thieves, and outlaws–life lived on the hard earth at the roots of trees; seeking alms-food from villages; and looking for something to wear, often pulling rags off the corpses whose jackal-chewed remains littered the charnel grounds.

“It was life held like a brief candle-flame in the vast stormy night of sickness, danger, and death. Only a few ventured into this way fo life, some of dubious sanity, some quiet saintly, but all were held in a mixture of fear and awe by the ordinary folk of town, clan, and family.”

Now This

The orthopedic surgeon said: There’s a gel we could inject, but I don’t think it would help. Arthroscopic won’t do you any good. You can increase the naproxen to two tabs, twice a day, and I can write you a script for physical therapy, if you want. But those knees are going to need to be replaced.

Bruises

by Jane Hirshfield

In age, the world grows clumsy.

A heavy jar

leaps from a cupboard.

The suitcase has corners.

Others have no explanation.

Old love, old body,

do you remember–

carpet burns down the spine,

gravel bedding

the knees, hardness to hardness.

You who knew yourself

kissed by the bite of the ant,

you who were kissed by the bite of the spider.

Now kissed by this.

On Doing What Needed to Be Done

Last summer I was thrilled and inspired by New Orlean’s Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech given just before the Confederate statues were taken down. (I posted an excerpt here.)

Last summer I was thrilled and inspired by New Orlean’s Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech given just before the Confederate statues were taken down. (I posted an excerpt here.)

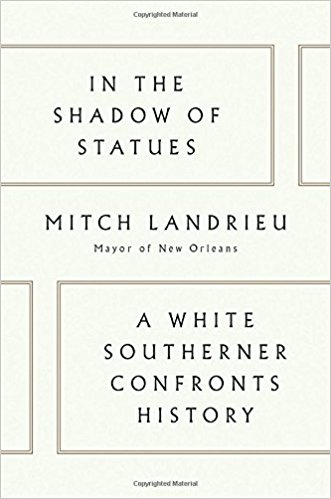

And now I’m even more thrilled that Mayor Landrieu has written a book about these events. It’s titled In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History.

Wow.

Here’s an excerpt from the prologue:

Here I was, mayor of a major American city in the midst of a building boom like no other, filled with million-dollar construction jobs, and I couldn’t find anyone in town who would rent me a crane. Are you kidding me?!

…The people of the city of New Orleans, through their elected government, had made the decision to take down four Confederate monuments, and it wasn’t sitting well with some of the powerful business interest in the state. When I put out a bid for contractors to take them down, a few responded. But they were immediately attacked on social media, got threatening calls at work and at home, and were, in general, harassed. This kind of thing normally never happens. Afraid, most naturally backed away. One contractor stayed with us. And then his car was firebombed. From that moment on, I couldn’t find anyone willing to take the statues down.

I tried aggressive, personal appeals. I did whatever I could. I personally drove around the city and took pictures of the countless cranes and crane companies working on dozens of active construction projects across New Orleans. My staff called every construction company and every project foreman. We were blacklisted. Opponents sent a strong message that any company that dared step forward to help the city would pay a price economically and even personally.

Can you image? In the second decade of the twenty-first century, tactics as old as burning crosses or social exclusion, just dressed up a little bit, were being used to stop what is now an official act, authorized by the government in the legislature, judicial, and executive branches.

This is the very definition of institutionalized racism. You may have the law on your side, but if someone else controls the money, the machines, or the hardware you need to make your new law work, you are screwed. I learned more and more that this is exactly what has happened to African Americans over the last three centuries. This is the difference between de jure and de facto discrimination in today’s world. You can finally win legally, but still be completely unable to get the job done. The picture painted by African Americans of institutional racism is real and was acting itself out on the streets fo New Orleans during this process in real time.

In the end, we got the crane. Even then, opponents at one point had found their way to one of our machines and poured sand in the gas tank. Other protesters flew drones at the contractors to thwart their work. But we kept plodding through. We were successful, but only because we took extraordinary security measures to safeguard equipment and workers, and we agreed to conceal their identities. It shouldn’t have to be that way….

This has been a long and personal story for me. I hope that this book meets each reader wherever they are in their own journey on race, and that my own story gives each of them the courage to continue to move forward. I hope that this book helps create hope for a limitless future. Now is the time to actually make this city and country the way they always should have been. Now is the time for choosing our path forward.

***

Amen!

Reading Outside the (Color) Line

One of the (many) things that has changed in my life since participating in the Waking Up to Whiteness program (which I posted about here) is that I’ve started to notice how much of what I read is written by white people, about white people. Which is understandable — since I’m white. But so limiting!

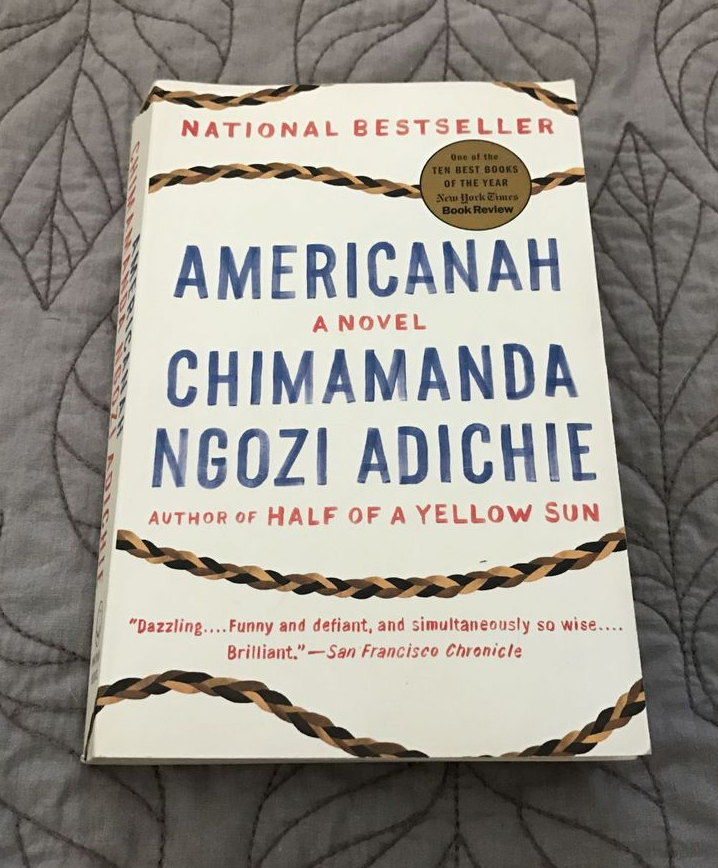

Now I’m really making a conscious effort to break out of that pattern. To which end: I just started reading Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

I picked it because the New York Times recently listed it as one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

(Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday, which I just finished reading and posted about here, was also listed. Click here for the compete Times listing.)

In the past, I probably wouldn’t have even noticed this novel. Which would have been a shame, because it’s TERRIFIC!!!

Here’s a sample from the first few pages:

“The man standing closest to her was eating an ice cream cone; she had always found it a little irresponsible, the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men, especially the eating of ice cream cones by grown-up American men in public. He turned to her and said, ‘About time,’ when the train finally creaked in, with the familiarity strangers adopt with each other after sharing in the disappointment of a public service. She smiled at him. The graying hair on the back of his head was swept forward, a comical arrangement to disguise his bald spot. He had to be an academic, but not in the humanities or he would be more self-conscious. A firm science like chemistry, maybe. Before, she would have said, ‘I know,’ that peculiar American expression that professed agreement rather than knowledge, and then she would have started a conversation with him, to see if he would say something she could use in her blog.

“People were flattered to be asked about themselves and if she said nothing after they spoke, it made them say more. They were conditioned to fill silences. If they asked what she did, she would say vaguely, ‘I write a life-style blog,’ because saying, ‘I write an anonymous blog called Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black’ would make them uncomfortable.

“She had said it, though, a few times. Once to a dreadlocked white man who sat next to her on the train, his hair like old twine ropes that ended in a blond fuzz, his tattered shirt worn with enough piety to convince her that he was a social warrior and might make a good guest blogger. ‘Race is totally overhyped these days, black people need to get over themselves, it’s all about class now, the haves and the have-nots,’ he told her evenly, and she used it as the opening sentence of a post titled ‘Not All Dreadlocked White American Guys Are Down.'”

Entering the Stream

More on “personality view” from Ajahn Sucitto. (I know this post is really long, but I just couldn’t bear to cut it.)

“The Buddha presented 10 “fetters” or “knots” that are released at Awakening. Awakening has several stages to it. At the first stage, the first three fetters all go at the same time. It’s not 1, then 2, then 3… because the first three fetters are really aspects of the same experience.

“The first is sakayaditthi (literally: ‘the view of being in this body,’ which is generally translated as ‘personality view‘). This is the isolated individual. It’s the belief in the individual as a separate reality and also that it can provide a good foundation.

“But as we practice, probably we begin to recognize that the personality is something that we have to be able to release, rather than to establish as a foundation. It doesn’t mean that there’s no sense of self. It means that we can begin to recognize that the personality is kind of like a structure, or a series of mental actions and perceptions that have been established through past karma and particularly through the social/domestic experience. So our personality forms as a response to the world around us.

“And so this is very much associated with the second fetter, attachment to ‘systems and customs,’ because that’s exactly what the personality gets indoctrinated into — systems and customs: Do this, do that. Get a job, get a mortgage, get two-point-five kids, get a dog, be happy. That’s it.

“I’m being humorous, of course. But there’s also nationalism, religious dogmatism — these are also aspects of systems and customs. What it leads to is a certain automatic quality, where we operate automatically according to certain socially generated norms.

“Neither of these mean that you don’t have any personality. Personality is a natural form. The citta (heart) develops a sort of skin, you could say, to interact in the world. But you don’t believe that that’s your final “statement”. That’s just the clothes you wear, you might say.

“I want to get that clear because in terms of people with a lot of deep practice, or who are said to be or understood to be or seem to demonstrate quite realized qualities — they still have a personality. But often it can be that they can kind of turn it off, as well. It’s not a fake thing. It’s just that when there’s a time for interaction, the personality is the appropriate way to interact.

“But their personality is often quite light and flexible. It’s appropriate. They’re not trying to boost it, or emphasize it.

“And certainly they can use systems and customs as is appropriate, as is suitable. Because if handled properly, systems and customs can be a ground for harmony: Let’s all do it this way. Fine. Then we know where we are and we don’t have to concern ourselves too much about these behavioral things.

“Also someone like this is aware of the rationale behind systems and customs. For the sake of harmony or out of mutual respect or imbued with conscience and concern, one can use a meditation system without it turning into: This is it. It’s the only way. I’ve got to be good at this… Instead: Ah, this is actually providing the ground for calming or steadying or it’s making me realize where the hindrances are. This is good! And one can use a range of those systems. One really sees the value of them and can use them rather than being disoriented without them or being dogmatic about them.

“This can be because the citta has realized something beyond the level of personal behavioral experience. It’s realized something deeper than that.

“So therefore it doesn’t have the third fetter: doubt (or lack of confidence). One is confident that this ‘me’ is not something I really have to concern myself about too much because there’s something more important here than my personality and what people think of me and whether I look good or…

“You also might say that this sense of right and wrong is much softer. Right and wrong often applies to dogmatic apprehension of experience: This is right and this is wrong. Instead one might say: This doesn’t seem to be very fitting right now.

“But the person where these fetters are really deeply embedded will have a lot of personality issues. Often complaining about themselves; the inner tyrant experience; critical mind; going on and on worrying about themselves. And also doing it to other people: She’s this and he’s that. Always focusing on the personalities of other people as a big issue.

“Without that, we can get on with a whole range of people because we’re not really making personality the main thing. So this makes life a lot broader and more expansive.

“That really is the stream-enterer, but they still have things like sense-desire, ill-will, residences….. You know, they’ve still got stuff!

“I think that’s really helpful because if you’re aiming for total purity on day one, or you’ve got to let go of all your attachments, that’s a big ask. But that’s not it.

“So the next two fetters are: resistance (or irritability) and sense-desire. One’s mind is heated by the qualities of sense desire and one’s mind is also irritable. It’s not permanently irritable, but certainly you can sense that irritability to things, and resistances. Likes and dislikes. Even the once-returner [the second stage of Awakening] has still got that to a certain degree. Then that fades, wanes, as the foothold on what we’ll call the Deathless becomes more assured, so that one is experiencing a sense of comfort in it.

“The first realizations, or aspects of realization, are really not so much about feeling that great. The first thing that’s established, actually, is a sense of security. Or stability. Which is what ‘confidence’ means. Or ‘lack of doubt.’ You’ve touched something and you know… you don’t necessarily always feel great and comfortable and wonderful… but you know: This is it. And because of that, then the path is established. You know. Even though things are still somewhat uncomfortable — preferences, irritability — still you know: I have confidence; There is this; There is this place of refuge.

“So the stream-enterer definitely has a refuge, a foothold on it. That’s why it’s called ‘entering the stream.’ They’re just getting their feet in it. They’re not totally buoyed up by it. So it’s just: There is a stream. It doesn’t mean one necessarily is completely immersed in it. [laughs] So the irritability and sense-desire are still there to a degree. But this doesn’t get in the way of what they’re doing.

“Another fetter is the attachment to meditation qualities: to fine mind-states, and then to even subtler mind-states — absorptions and calm and ease and spaciousness. Those are another two fetters. The stream-enterer still hasn’t really broken or released those.

“And there’s ‘conceit‘ — conceiving oneself to be something, either better or worse or the same-as. Having oneself as a concept, a ‘perceptual self’ you might say. Conceiving oneself as anything really — enlightened, half-enlightened, somewhat enlightened. That’s why the realized people just don’t say anything about being enlightened, generally. Because it doesn’t really make sense. [laughs] You just say: Suffering has stopped.

“Then ‘restlessness,’ where the mind has still got some association with the conditioned realm. The conditioned mind is always shifting and moving. There’s an association with that, so the mind is being stirred. And the last is ignorance, or the lack of full comprehension. These then are not released — yet.

“But stream-entry is perhaps the major breakthrough. The Buddha pointed to a mountain and then he pointed to the dirt under his fingernail and he asked: What do you think is greater — the amount of earth in that mountain or the amount of earth under my fingernail? And of course, the bhikkhus: Surely Lord…. [laughs] And then the Buddha said: Well, the amount of earth in that mountain, that’s what you shift at stream entry. And what I have under my fingernail, that’s the rest of it. So it’s considered a major breakthrough because then it is said that one is not going back. It’s going to continue. It’s going to deepen.

“The aim then is to keep referring the heart to that, keep establishing it, keep acknowledging what drags one out of it, and increasing the sense of enjoyment in it, and the comfortableness. And then working on the subsidiary fetters.

“You can notice what bothers you. So if you’re still worked up about him and her and myself and this-that-and-the-other, there’s some ‘personality view’ still there. Or if you momentarily get these irritable mind-states or a tendency to be critical, then you know that and your aim is to work on that.

“Even though stream-entry is a major breakthrough, a stream-enterer isn’t always clear about it. Because it’s not that solid. It’s solid in the way that it’s not going to turn back, but you can’t really feel fully enriched by it. Stream-enterers can still misbehave. But because they’re not attached to their personality, they can acknowledge it. They’re not defensive because they’re not trying to present themselves as an ideal person any more. Which is a great help.”

***

This excerpt has been lightly edited for clarity and readability. It is Ajahn Sucitto’s answer to the question: “How would you characterize freedom from sakayaditthi (personality view)?” Click here for the full Q&A session.

A Completely Different Point of View

(a little bit more from Leonard Cohen at the Zen monastery):

Religious Statues

from Book of Longing

After a while

I started playing with dolls

I loved their peaceful expressions

They all had their places

in a corner of Room 315

I would say to myself:

It doesn’t matter

that Leonard can’t breathe

that he is hopelessly involved

in the panic of the situation

I’d light a cigarette

and a stick of Nag Champa

Both would burn too fast

in the draft of the ceiling fan

Then I might say

something like:

Thank You

for the terms of my life

which make it so painlessly clear

that I am powerless

to do anything

and I’d watch CNN

the rest of the night

but now

from a completely different

point of view

The More You Learn…

I just finished reading Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday, and now all I want to do is to read it all over again.

I won’t attempt to write a review. The New York Times has a wonderful one here. So does NPR, here. And The Atlantic, here. Instead, I’ll just say that the experience of reading this book has taught me way more than I ever thought possible about a situation that I thought I already knew way too much about, and about a totally different situation that I knew I knew nothing about, but didn’t know just how much of this “nothing” I knew nothing about.

*** The book is written in three sections. The first is titled: Folly. It begins like this:

Alice was beginning to get very tired of all this sitting by herself with nothing to do: every so often she tried again to read the book in her lap, but it was made up almost exclusively of long paragraphs, and no quotation marks whatsoever, and what is the point of a book, thought Alice, that does not have any quotation marks?

She was considering (somewhat foolishly, for she was not very good at finishing things) whether one day she might even write a book herself, when a man with pewter-colored curls and an ice-cream cone from the Mister Softee on the corner sat down beside her.

“What are you reading?”

Alice showed him.

“Is that the one with the watermelons?”

Alice had not yet read anything about watermelons, but she nodded anyway.

“What else do you read?”

“Oh, old stuff, mostly.”

They sat without speaking for a while, the man eating his ice cream and Alice pretending to read her book.

Two joggers in a row gave them a second glance as they passed. Alice knew who he was–she’d known the moment he sat down, turning her cheeks watermelon pink–but in her astonishment she could only continue staring, like a studious little garden gnome, at the impassable pages that lay open in her lap. They might as well have been made of concrete.

“So,” said the man, rising. “What’s your name?”

“Alice.”

“Who likes old stuff. See you around.”

*** The second section is titled: Madness. It begins like this:

Where are you coming from?

Los Angeles.

Traveling alone?

Yes.

Purpose of your trip?

To see my brother.

Your brother is British?

No.

Whose address is this then?

Alastair Blunt’s.

Alastair Blunt is British?

Yes.

And how long do you plan to stay in the UK?

Until Sunday morning.

What will you be doing here?

Seeing friends.

For only two nights?

Yes.

And then?

I fly to Istanbul.

Your brother lives in Istanbul?

No.

Where does he live?

In Iraq.

And you’re going to visit him in Iraq?

Yes.

*** The third section is titled: Ezra Blazer’s Desert Island Discs. It begins like this:

Interviewer: My castaway this week is a writer. A clever boy originally from the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he graduated from Allegheny College swiftly into the pages of “Playboy,” “The New Yorker,” and “The Paris Review,” where his short stored about postwar working-class Americans earned him a reputation as a fiercely candid and unconventional talent. By the time he was twenty-nine, he had published this first novel, “Nine Mile Run,” which won him the first of three National Book Awards; since then he’s published twenty more books, and received dozens more awards, including the Pen/Faulkner Award, the Gold Medal in Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, two Pulitzer Prizes, the National Medal of Arts, and just this past December–“for his exuberant ingenuity and exquisite powers of ventriloquism, which with irony and compassion evince the extraordinary heterogeneity of modern American life”–literature’s most coveted honor: the Nobel Prize.

***

Somewhere in the middle of the first section, I underlined this: The more you learn, thought Alice, the more you realize how little you know.

Right.

Conflict and Comparison

(continuing from yesterday’s post with excerpt from Ajahn Sucitto’s Q&A on the mental “fetters” that bind us to suffering)

The second fetter, attachment to rites and rituals (silabbata-paramasa), has to do with — not just rituals, lighting incense, or praying — but everything that’s automatic. It’s systems and customs. Any kind of system or custom.

Language is a system. It’s a series of sounds and words, but it’s a system, a custom. Everybody is operating according to systems and customs. For example, everybody goes to work at this time or everybody eats their meal at this time. Everybody’s following some kind of ritual/system/custom. These are things we operate with, but really, in truth, there’s no day or night, there’s no Monday or Thursday — that’s just the convention. We think: “Oh, this is Thursday, I have to do this. Or I can only do this on Sunday. Or it’s six o’clock!” But there’s no such thing as six o’clock. It’s just the convention. And when one gets attached to these things, then we live life like a robot. Like a puppet that’s moved along. This is a considerable fetter.

Doctrines can also be part of that. Even meditation systems can be things we get attached to: “This is the right way. I’m going it right. He’s wrong.”

The quality of these always separates us. So even when you call yourself a “Buddhist”, it’s tricky. Buddhism a good system, but it’s a system. And actually, there are no “Buddhists”, really, there’s just Dhamma practice. We can call ourselves “Buddhists” when we have to write something down on an official form, or whatever. So people know that this is the label and it probably means we’re good people. But we also understand this is just a system and a custom. It has to be seen in the light of: When does it become useful? When does it become something where we quarrel? As in: Who’s better — Buddhists or Christians? Mahayana or Theravada? And in meditation: Which practice style do we do? Mahasi Sayadaw or Ajhan Chah or U Pandita or U Tejaniya or Zen? Then we get stuck in these things.

The Buddha didn’t teach any of that. He said: “Purify the heart.” Is there a system for that? [laughs]

So attachment to systems and customs sets us apart from each other. And then we find there is comparison and conflict. There’s no liberation where there is comparison and conflict. There’s no ending of suffering where there’s comparison and conflict. There’s no ending of stress where there’s superior and inferior. Where there’s men and women. There’s no ending of it.

It only ends when you come to: Let go of that. There is a point at which these are relevant, and there’s a point where they’re irrelevant. For liberation, you must realize the depth where these things that separate us no longer occur. Because there’s no suffering in that. There’s no stress in that. There’s no holding on in that. There’s no need to hold it.

And doubt (vicikiccha), which is the final fetter that’s eliminated at “stream-entry”, is just the lack of understanding. Where we don’t really realize that there is a place beyond thought and beyond attachment, that you can rest in.

Because of not knowing that, we’re always creating something to hold onto, something to name, something claim, something to dispute. Because we haven’t really understood that there’s a place where none of that need happen. And where that doesn’t happen, there’s confidence. Confidence that isn’t about being right. It’s about having no right or wrong, just: This is true; It’s like this.

A lot of people are looking for the right opinion. You don’t need an opinion. Well, sometimes you do. But with the truth, you don’t need an opinion.

You just need to know: This is where the suffering stops; the stress stops; the pressure stops; the holding on stops. This is where it stops. And this is where it happens; this is what causes it to happen; and this is what causes it to cease.

Now any system, any way you can do that — that’s fine. That to me is the Dhamma world. Who’s in it? I don’t know. Buddhist? Sufis? Jews? I don’t know. But if you can get there: Good!

***

(You can listen to the entire Q&A session with Ajahn Sucitto here.)

Personality View

I love the very accessible explanation of “personality view” (sakkayaditthi), which Ajahn Sucitto gave during a recent Q&A session in response to a question about whether or not a “stream-enterer” could ever lose contact with the Dharma. (“Stream-enterer” is the term traditionally used to describe someone who has reached the first stage of enlightenment.) Ven. Sucitto says:

“The stream-enterer has some realization, but not complete realization, so, yes, they could lose the precepts. But the stream-enterer is of the quality that they could acknowledge this — and return.

“The stream-enterer has not eliminated greed and hatred, or passion and craving. But they have eliminated the personality view. The personality view is gone, so they’re not proud; they’re not defensive; they’re not justifying themselves. The stream-enterer is always someone who can be corrected. But they can make mistakes.

“The stream-enterer has essentially lost the first three “fetters”. The first of these is sakkayaditthi (personality view), which is the belief in being an independent entity. A personality. Meaning that the thing that makes us different — we take that to be the foundation of our life. Rather than taking the thing that makes us NOT different.

“That which makes us different — different faces, different attitudes, different personalities — that becomes the reference point. With personality view, that’s what I take a stand on; that becomes what I take as most important. That’s always going to cause division. Because there’s only one like ME!

“But if your reference point is the universal — which is the quality of goodwill, the quality of truthfulness, the quality of patience, etc. — there’s no person in that.”

***

The next two “fetters” are: silabbata-paramasa (attachment to rites and rituals) and vicikiccha (usually translated as “skeptical doubt”.) I’ll post Ajahn Sucitto’s explanation of those tomorrow.

Can’t wait? Click here to listen.