Through Effort and Grace

“When we can open our hearts and work with what we’re given, loving what’s before us, life stays possible. Then, through effort and grace, we do what we can with what we have. And when exhausted by all that’s in the way, we’re faced with the chance to accept and love what’s left, which is everything. This is how we discover that Heaven is on Earth.”

–from Things that Join the Sea and the Sky: Field Notes on Living, by Mark Nepo

Me. Me. Me. Me. Me. Me. ME!

One of my dharma buddies sent me a great series of talks by Tenzin Palmo, a British woman who spent twelve years practicing in a remote cave in the Himalayas and was the first to receive full bhiksuni ordination in the Tibetan tradition. (Thanks Betsy!)

One of my dharma buddies sent me a great series of talks by Tenzin Palmo, a British woman who spent twelve years practicing in a remote cave in the Himalayas and was the first to receive full bhiksuni ordination in the Tibetan tradition. (Thanks Betsy!)

I haven’t listened to them all, but I plan to. Yesterday I listened to: Teaching on the Eight Verses of Mind, in which Palmo says:

“In Buddhism, pride means thinking we are superior to other people, but it also means thinking that we’re inferior to other people.

“Because if I think: Oh, I’m the most stupid person here; I’m hopeless; I can’t do anything; All these people, they’re so wonderful…. Or when you’re on retreat: Oh, everybody else is deep in the first jhana or at least some samadhi, I’m the only one that’s been caught up in these wondering thoughts…. That is not humility. That’s just the inverse of the ego, beating itself up.

“The ego is very happy to be miserable. Because, if we are miserable (especially full of self-pity) about how awful and hopeless and stupid we are…. what are we thinking about?

“Me. Me. Me. Me. Me. Me. Oh poor Me. Oh stupid Me. Oh hopeless Me. — ME!”

***

She nailed that one.

The whole talk is really quite wonderful. It’s long, but it’s worth it. (The excerpt above begins at about the 29 minute mark.) Click here to listen.

Heartwood

Our Dharma Book Group meets tonight (we’re reading In the Buddha’s Words, by Bhikkhu Bodhi), and it looks like our discussion will take us into The Greater Discourse on the Simile of the Heartwood (MN 29), which includes one of my favorite quotes from the Buddha.

Here’s what Bhikkhu Bodhi has to say:

“The sutta is about a ‘clansman’ who has gone forth from the household life into homelessness intent on reaching the end of suffering. Though earnest in purpose at the time of his ordination, once he attains some success, whether a lower achievement like gain and honor or a superior one like concentration and insight, he becomes complacent and neglects his original purpose in entering the Buddha’s path. The Buddha declares that none of these stations along the way — not moral discipline, concentration, or even knowledge and vision — is the final goal of the spiritual life…”

The Buddha says, “But it is the unshakeable liberation of mind that is the goal of this spiritual life, its heartwood, and its end.”

***

“Unshakeable liberation of mind.” I just love that!

Something Naturally Arises

Another excerpt from Ajahn Sucitto, this time from a beautiful little talk (less than 12 minutes long!) in which he suggests “entering into a relational field” — instead of reacting to things in terms of “subject-and-object.” (Thanks for pointing me to this one, Carolyn.)

Sucitto says, “Be on guard for any time we see something as an ‘object’ — especially if it’s a person — (oh, her…or he’s my boss…or she’s my wife…). As soon as you get one of those: Uh-oh! You’ve just whistled up a problem! Because objects in that experience are always saturated with unconscious craving, resistance of various kinds, and mental factors we haven’t acknowledged.

“When that happens, it’s time to: Stop. And check. Not the object or the subject, but: What’s the relational tone of mind? Is it ill will; is it regret; is it nagging; is it hungry; is it blaming; is it comparing; is it ‘should-be’; is it ‘if only he was…’

“Ask what is happening in that relational field. And then: could that activity just stop….and take a break — a break from suffering!

“Then from there, take a breather and ask: What seems important now? What’s the one important gesture now?

“Then from that place, you can just… have a little bit of give. Because: Why not? And it makes you feel good!

“The more you can enter that kind of place, the more you can get all kinds of growth, development, understanding, realization… Shifts can occur. In relationship with other people. In relationship with yourself!

“….So, entering the relational field: It’s always kind of fresh because it’s not pre-conceived. Even a good strategy like: OK, I will be loving and peaceful. That’s a nice idea, but it’s an ideal. And where does that come from? [laughter]

“Instead, could something naturally arise…through the relinquishment of mental obstructions. That’s really a mystical and religious experience — when something naturally arises — which is not myself.

“And it happens. Definitely. It happens.”

***

This excerpt is edited and condensed. I highly recommend listening to the whole talk (and doing it more than once!). Click here.

Yet Another Reason to Know How to Meditate

A friend just told me she heard this on BBC news (thanks, Judy):

Thailand cave rescue:

Meditation led by coach helped the boys survive terrifying ordeal, family say

“The 12 Thai boys and their football coach who were trapped in a cave in Thailand got through the ordeal by practicing meditation, family members have said.

“According to a mother of one of the boys, the team were meditating in the widely shared video of their discovery by two British divers.

“‘Look at how calm they were sitting there waiting. No one was crying or anything. It was astonishing,’ she told the Associated Press.

“The coach who was rescued from the cave on Tuesday, trained as a Buddhist monk for 12 years before he decided to coach the Wild Boars soccer team.

“‘He could meditate up to an hour,’ said his aunt, Tham Chanthawong. ‘It has definitely helped him and probably helps the boys to stay calm.'”

***

Wow, you just never know when it’ll come in handy!

(This story appeared yesterday in the Evening Standard. To read the full article, click here.)

Where Am I Now?

More from Ajahn Sucitto:

“Whenever you feel yourself getting pulled, that’s the most important time to — pause. Pause for just 20 seconds…or a minute…and ask: Where am I now?

“Not: What should I do? But: Where am I now?

“You might think, ‘I’m in a restaurant. I’m in an office.’ No, that’s just what it looks like. That’s what your eyes can see. That’s what your thinking mind can tell you. But the real question is: Where do you feel your presence? Where is your presence now?

“Presence is a sense of firmness, of stability. It’s always here. And it’s always being dissipated into the sense fields. So when we ask, “Where am I now,” this is not really asking for a verbal response. It’s pointing to the quality of the citta — of Awareness as Presence. We can notice the trembling, or the questioning or the feelings or the sensations — they’re all moving and changing.

“Meanwhile, with all that, as one is acknowledging that it’s all moving and changing — what is it that acknowledges the moving and changing? It’s: Presence. The sense of presence of the citta, as a simple quality of being. There’s a stillness there. A point of stillness.

“It may sound difficult when I try to put it into words, but we can — pause — and ask: “Where am I?” Or: “What’s really here? And within this realm of sights and sounds and thoughts and energies and emotions and pushes and pulls and moods and impressions — Presence is here.

“Take your time with that. This is Being. Being is always exactly the same. Being doesn’t change in time. Being is not the person. Being is not the moods. Being is not the thoughts. Being is not the activities. Being is just being here. And that’s a refuge. That’s an island in the middle of the stream, in the middle of the flood. You can return to that. And then from here, you can ask: “What’s useful? What’s important? What is the most skillful thing to do, at this particular time?”

***

This is just an excerpt from Ajahn Sucitto’s talk, The Duties of Heedfulness, beginning at about the 26 minute mark. I highly recommend listening to it in its entirety. He’s talking about how to make daily life into a meditative practice! Click here to listen.

All Our Relations

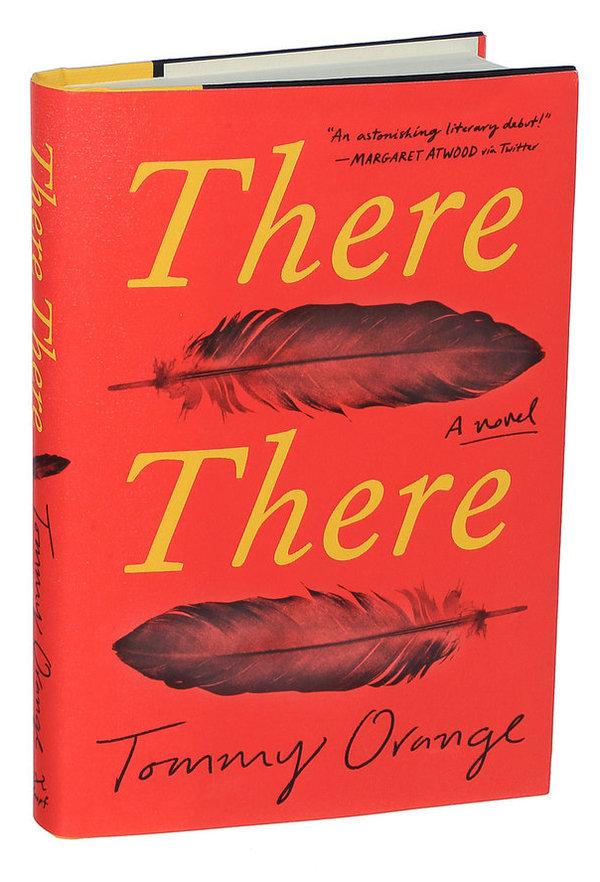

I just started reading There There, by Tommy Orange, and already I feel my heart/mind opening, shifting, changing. Here’s an excerpt from the Prologue:

I just started reading There There, by Tommy Orange, and already I feel my heart/mind opening, shifting, changing. Here’s an excerpt from the Prologue:

“Urban Indians were the generation born in the city. We’ve been moving for a long time, but the land moves with you like memory. An Urban Indian belongs to the city, and cities belong to the earth. Everything here is formed in relation to every other living and nonliving thing from the earth. All our relations.

“The process that brings anything to its current form–chemical, synthetic, technological, or otherwise–doesn’t make the product not a product of the living earth. Building, freeways, cars–are these not of the earth? Were they shipped in from Mars, the moon? Is it because they’re processed, manufactured, or that we handle them?

“Are we so different? Were we at one time not something else entirely, Homo sapiens, single-celled organisms, space dust, unidentifiable pre-bang quantum theory? Cities form in the same way as galaxies. Urban Indians feel at home walking in the shadow of a downtown building. We came to know the downtown Oakland skyline better than we did any sacred mountain range, the redwoods in the Oakland hills better than any other deep wild forest. We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers, the howl of distant trains better than wolf howls, we know the smell of gas and freshly wet concrete and burned rubber better than we do the smell of cedar or sage or even fry bread–which isn’t traditional, like reservations aren’t traditional, but nothing is original, everything comes from something that came before, which was once nothing.

“Everything is new and doomed. We ride buses, trains, and cars across, over, and under concrete plains. Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere.”

***

Wow. This, too, is Dharma.

Try: Seeing a Tree

Suggested Exercise, from Ajahn Sucitto:

Suggested Exercise, from Ajahn Sucitto:

“One thing that’s very important in all meditation practice is a sense of changing speed. Because in the change of speed you come out of that blurred, impulsive rush, whereby you go down the channels [of habitual patterns]. So this is about a change of speed… or calming, if you like…. or sustaining attention.

“I’d like to suggest that you practice this for a while, maybe 30 minutes, outside… it’s something I quite appreciate doing… just let your eyes rest upon, say, a tree or something like that… Stay with it visually, just let your eyes stay there. And you will notice how, if you stay with that for 5 or 10 minutes (a sustained period of time) — you’ll notice all the changes that occur in that simple experience: Seeing a Tree.

“So, let’s say you look at it and expectation occurs. OK, expectation — that occurs. Then you notice a detail. Oh, that’s kind of interesting — that occurs. Then maybe appreciation. What a lovely tree — that occurs. And then, Well, I think I’ve done that, had enough — that occurs. [laugher]

“And then maybe the visual thing starts to dilate. In other words, you see tiny details and you see the big field, and if you keep your eyes on it, it will start to vibrate (visually). And it becomes much more amorphous… and you stay with that, until eventually — tree???

“The word ‘tree’ no longer applies.

“This is when, in a way, what’s happened is: the object-forming tendency, which goes on for a period of time, starts to…. Well, I’ve seen that object… It’s done its job. It’s said, Oh, that’s a leaf; that’s a twig; that’s bark; that’s green; that’s black; that’s a color; I like that…. and eventually it’s, Well, I’ve said all that, and it starts to not have anything more to say. [laughter]

“And then, one feels more touched by it.

“As the object-forming and the categorizations wear out, or receded… one gets more and more touched… There’s an intimacy, of presence, that occurs. I don’t know what it is, but I’m feeling really attentive, and awake, to this. And a sense of appreciation occurs.

“These are the sorts of modalities that can occur, because all these tendencies… these aggregates… which seem so concrete, are only made so by the rapidity of the juggling act that keeps them all binding together. And the passion for it. The excitement to make it happen.

“If you stay with something long enough, it starts to… the object-forming tendencies begin to… you know…. wear out.

“But it’s not that there’s nothing there. It just becomes more… un-named. And something is very bright about that.

“So I would suggest you take some time and see if you can find… either standing, or a bench or something whereby you may be able to sustain… It’s not a matter of having your eyes rigidly focused, but keep a sustained attention. You can look around it, look up and down… pause… slow… slow your eye movements down… as if you are tasting with your eyes, every grain of visual experience, every little fleck of it.

“Yeah.

“This is all seeing. It is just seeing. Until the mental configurations begin to pass away.

“OK?”

***

OK!

This is the entire transcript (very lightly edited) of a lovely little less-than-5-minute talk by Ajahn Sucitto, title: A Suggested Exercise. Listen to it here.

Standing Like a Tree; Breathing Like a Buddha

This post is long, I know, but bear with me. It’s another excerpt (which I just couldn’t cut!) from the terrific Qi Gong and Anapanasati talk by Ajahn Sucitto.

This post is long, I know, but bear with me. It’s another excerpt (which I just couldn’t cut!) from the terrific Qi Gong and Anapanasati talk by Ajahn Sucitto.

“In teaching Mindfulness of Breathing over many years, and listening to people in interviews, so many of them say to me, ‘Aggh… I can’t do it! My brain is thinking all the time. I feel so tense and tight. I’m trying to focus on this point on my nostrils — I can’t find it at all. I can’t meditate!

‘I try really hard to do it and I’m getting more and more tense. I just give up. I can’t manage it. I was breathing OK until I started being mindful of it! I could breathe in and out quite normally and then when I started being mindful of it, I started getting tight and constricted; I felt pain; I felt uncomfortable; I felt stressed, and you know… Surely this can’t be right! The Buddha says: I call this a comfortable abiding, a pleasant abiding, it makes one feel fresh, one’s eyes feel good… This can’t be the same thing. What’s happening?’

“What’s happening is: the mind is affecting the breath. Before we brought it to our attention, breathing wasn’t a problem. We had other problems — also which were because of our attention — like thinking about this, thinking about that, and our attitudes.

“But very often, for people these days, it’s the ‘work mind’ that comes forward. The ‘work mind’ rushing to get things done; the ‘work mind’ anxious about not doing it good enough; the ‘work mind’ desperately in a hurry to try to achieve results; the ‘work mind’ tightening up to make sure we’ve got it exactly the way it should be. The ‘work mind’: stress, stress, stress, stress, stress. The mind gets conditioned into that kind of behavior. Anything we think is important, anything we think we really should achieve — the ‘work mind’ gets hold of it.

“You were breathing OK until you started to think it was important, and you thought it was going to give you good results. Important! Good results! Ahhh: go to work.

“And it IS important. We DO want good results. There IS certainly a process, and a progress – so it must be ‘work’, right? I don’t think so….

“In the Buddha’s time there wasn’t that ‘work mind’. They could certainly put energy in, but it was not that same compulsive, tight, up-in-your-head state of the ‘worker,’ who lives up behind the eyes and the forehead….

“We think: ‘OK, anapanasati, right — let’s get to work on that. Have we got it in our heads? Tighten up the mind! Tighten up the face!’

“We think this is concentration. The English word “concentration” CAN be applied to that. But that’s not samadhi. There’s no piti (happiness). No sukkah (ease, comfort). Those are not there.

“And it is sad. Because there is a true sincerity, and a true determination, to cultivate the mind. But we’re doing it with the wrong energy. It’s the right idea, right theory, right aspiration, wonderful resolve! But we’re using the wrong energy.

“What the Buddha is saying is there’s a natural energy that happens by itself. Breathing in — happens by itself. Breathing out — happens by itself. There’s an energy flow there.

“This is what we should get in touch with. With the kind of quality of attention that can maintain that focus. It’s not a focus that’s up in our forehead, which is so often where we assume it should be. We call it ‘watching the breath.’ Watching the breath? I’ve never seen a single breath! [laughter] Maybe on a very cold morning you might see a bit of mist. But I’ve never seen a breath. And I’ve been practicing this for years. When I look in the suttas, the Buddha never says ‘watch the breath’. He says ‘be mindful of breathing in and breathing out.’ He’s talking about being mindful of a process. Of breathing in and breathing out. So rather than this idea of being up in your head, with tightening your attention, maybe there’s another way that we can attend to that.

“And yes, there is.

“When you cultivate qi gong, you take a standing position. Like a tree. You bring your awareness particularly down to your feet, your ankles, and then you build it up, and gradually you spread your awareness from the soles of the feet, up through the body, through the spine, through the trunk, into the head. So that you cover the entire body and it is held in alignment. It’s called: balance. So you’re definitely attentive. You’re fully aware. Your mind isn’t wobbling or jumping around. It’s not dithering. Or confused. It’s actually firmly based on the entire body — as an energy form. We focus on the quality of balance.

“You can’t do that with a thought. You can’t think: balance. But your body can feel it. You can sense it. You come to realize this body is sensitive to a quality of balance, which itself is rather pleasant because there’s no stress in balance.

“Balance means the absence of stress. We’re not inclining to left or right, forward or backward. Balance is free of bodily bias. It’s free of pressure. When you’re in balance, you’re as stress-free as you can get.

“And there’s an energy there, that becomes apparent, that’s holding your body up. You learn to relax as much of your muscle as possible when you feel yourself being held. This is called: Standing Like a Tree. And the awareness is spread over the entire body. As you stand like that, sustaining that, there is a way of holding attention that is not narrow. It’s not constricted, it’s not conducive to stress, and yet it is very carefully held. You use a wide focus to do that.

“As you stand with that, you can begin to experience that there is this rhythm that starts to express itself and then… oh, there’s breathing! It’s a soft, rhythmic process. And you feel the energy of it. The vitality of it. You feel the way the whole body can feel it. That it’s no longer so constricted.

“So this gives a very good way in my experience of both improving bodily posture and changing one’s idea or impression of what the body is about. So that it’s not just this thing that we see with our eyes; it’s not the flesh body; it’s an energy body. It’s something that we begin to see is quite natural. It’s not mentally derived. It’s not an opinion or a view. It’s neither something we feel proud of or worried about. It’s free of those mental proclivities. It happens by itself. It’s naturally refreshing. And it’s naturally sustaining; it’s naturally calming; it’s naturally clearing of tension, dullness, restlessness — the hindrances! (The energies of the hindrances.) When the body is bright and open like that, the hindrances find it very difficult to get in. And so, you cultivate attention like that.

“The result of this is the body loses its tensions and congestions. It becomes a happy place for one’s awareness to sit, and breathing happens to you quite naturally. In other words, you don’t have to search for it. It comes to you. It comes into your awareness.

“You don’t have to decide where to focus; you feel it. You feel it as it’s happening. You’re training your mind to be more receptive to a natural process rather than being proactive and having to create something. This means that the mental obstructions and the mental proclivities — particularly the ones we experience as the mind set I call ‘work mind’ — these can be laid aside. And instead we feel the natural harmony, peace, and vitality that the Buddha must have experienced in his own process of awakening.

“So then we are truly breathing like a Buddha.

“How do you think the Buddha breathed? Chest open, shoulders back. Enjoying the bliss of breathing in and breathing out. This is nature. Nature manifesting in this way.”

***

Click here for the full recording. The excerpt above begins at about the 38 minute mark.

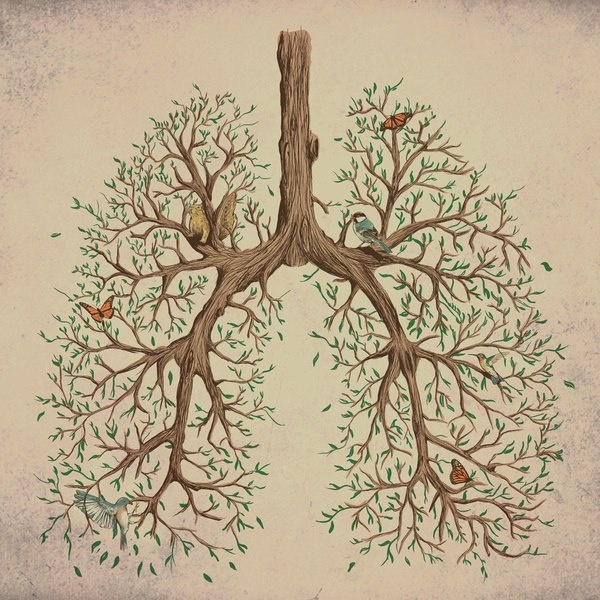

It’s Not Just Anatomy

A few days ago I found out that — for the fourth year in a row — my name did not get chosen in the lottery to attend Ajahn Sucitto’s month-long retreat at the Forest Refuge.

A few days ago I found out that — for the fourth year in a row — my name did not get chosen in the lottery to attend Ajahn Sucitto’s month-long retreat at the Forest Refuge.

Bummer.

But I consoled myself by listening to some of his recent talks on dharmaseed, where I came across this fabulous one, in which he begins by talking about using qigong as a support for the practice of mindfulness of breathing, and ends — well, in his words: “perhaps gone beyond the bounds of this particular talk.”

I highly recommend listening start-to-finish, but just to give you a hint of where he goes with this, here’s what he says at about the 31 minute mark:

“Breathing is energy. It’s not just anatomy. It’s an energy form that can be trained, moderated, and harnessed for very powerful spiritual purposes. In the Anapanisati Sutta (Teaching on Mindfulness of Breathing), it’s being used as the process of feeling the entire body, steadying and smoothing out the energies in the body. If we use more ordinary language, we might say our ‘nervous energy.’ Whether we’re jumpy, passionate, tense, or we’re experiencing a lack of energy — mindfulness of breath steadies and smooths all that.

“The Buddha says, This you do, and then you move on to the qualities of piti, which is a joyful, rapturous experience that arises when the body’s kayasankara [body energy] has been steadied. This is where the hindrances are put aside. So you experience the quality of piti — rapture, a brightened state — and then sukkha — a happy, comfortable state — and with these you also calm and steady the cittasankara — the emotional energy.

Sankara — meaning the formative quality. So with the body, it’s the formative quality that began when we were born. It’s been conditioned. It’s conditioned by birth. When you were in the womb, you weren’t doing it. As you come out, you switch it on. It’s a creation. It’s created by life itself. And it goes on until it’s finished — dead. That’s the creation of sankara.

Cittasankara is different. It’s generated. And it’s something we can moderate within this life. And in the Buddhist understanding, you can free the citta from sankara — without dying.

In fact: This Is the Deathless.”

***

Want to know more? Click here to listen.