This Wide Human Stream

Getting everything done before I catch a flight to California to go on retreat appears to be taking quite a bit longer than I had expected, so I won’t be posting again until sometime after I get back. (I return late on Aug 30.)

Getting everything done before I catch a flight to California to go on retreat appears to be taking quite a bit longer than I had expected, so I won’t be posting again until sometime after I get back. (I return late on Aug 30.)

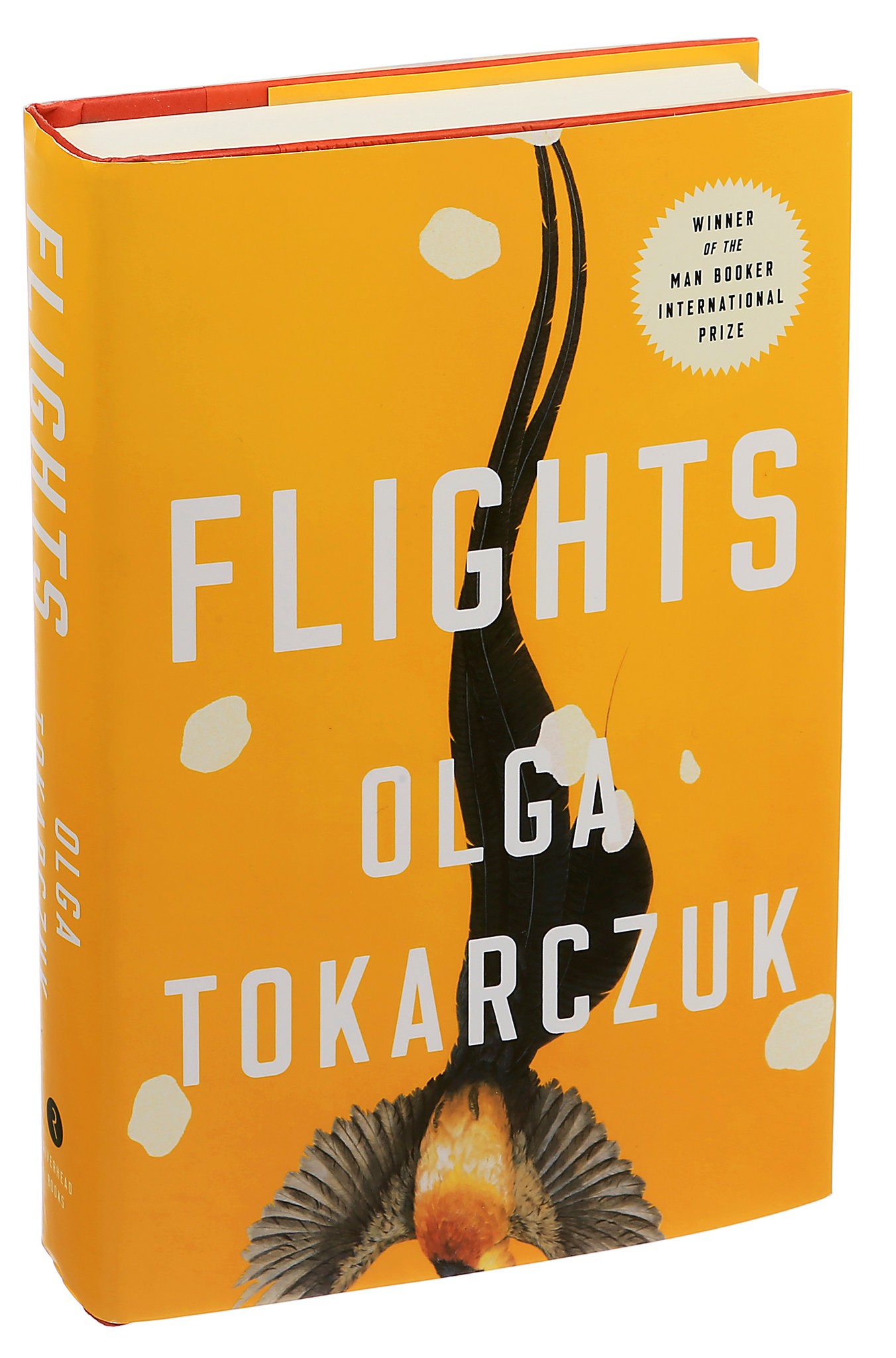

Usually before going on retreat, I leave you with a selection from my favorite inner travelogue, Invisible Cities, by Italo Calvino. This time I’d like to offer something similar, but different — from Flights, by Olga Tokarczuk, which won the Man Booker Prize this year and was just released today:

The Bodhi Tree

I met a person from China. He was telling me about the first time he flew to India on business; he had lots and lots of important individual and group meetings. His company produced quite complicated electronic devices allowing blood to be conserved longer-term, and allowing organs to be safely transported, and now he was negotiating to open up new markets and start some Indian subsidiaries.

On his final evening there he mentioned to his Indian contractor that he had dreamed since childhood of seeing the tree under which the Buddha had attained enlightenment — the Bodhi tree. He came from a Buddhist family, although at that time there could be no public mention of religion in the People’s China. But later, once they could avow whatever faith they wished, his parents unexpectedly converted to Christianity, a Far Eastern variety of Protestantism. They felt that the Christian God might come in handier to His followers, that He would be, let’s be honest, more effective, and it would be easier with Him to get some money and get set up. But this man did not share that view and kept the Buddhist faith of his ancestors.

The Indian contractor understood the man’s desire. He nodded and topped off his Chinese colleague’s drink.

In the end they all got pleasantly inebriated, getting out all the tensions of signing contracts and negotiations. With the last of their strength, wobbling on swaying legs, they went into the hotel sauna to sober up, since in the morning they still had work to do.

The following morning a message was delivered to his room — a little note with just one word: “Surprise.” Clipped to it the business card of his contractor. In front of the hotel stood a taxi, which now conveyed him to a waiting helicopter. After a flight of less than an hour the man found himself in the sacred spot where, beneath a great fig tree, the Buddha had attained enlightenment.

His elegant suit and white shirt vanished into the crowd of pilgrims. His body still preserved the bitter memory of alcohol, the heat of the sauna, and a rustle of papers signed in silence on the glass surface of the modern table. A scraping of a pen that left behind his name. Here, however, he felt lost, and helpless as a child. Women who came up to his shoulder, colorful as parrots, pushed past him in the direction this wide human stream was flowing. Suddenly the man was frightened by the thing that he repeated as a Buddhist several times a day, when he had time — the vow. That he would try to bring with his prayers and actions all sentient beings to enlightenment. Suddenly this struck him as utterly hopeless.

When he saw the tree, he was — to tell the truth — disappointed. He had not a thought in his head, nor any prayers. He paid the place its due homage, kneeling many times, making substantial offerings, and about two hours later, he returned to the helicopter. By afternoon he was back in his hotel.

Under a stream of water in the shower that washed from his body the sweat, dust, and strange sweetish smell of the crowd, the stalls, the bodies, the ubiquitous incense, and the curry people ate with their hands off paper trays, it occurred to him that every day he was witness to what had shaken Prince Gautama so: illness, old age, death. And it was no big deal. It produced no change in him; by now, to tell the truth, he’d grown inured to it. And then, drying himself off with a fluffy white towel, he thought he wasn’t even sure he truly wished to be enlightened. If he really wanted to see, in one split second, the whole truth. To peer inside the world as though by X-ray, to glimpse it in the skeletal structure of a void.

But of course — as he assured his generous friend that same evening — he was extremely grateful for this present. Then from the pocket of his suit coat he carefully extracted a crumbled leaf, which both men inclined over in rapt, pious attention.

***

See you in September!