Lost in Translation

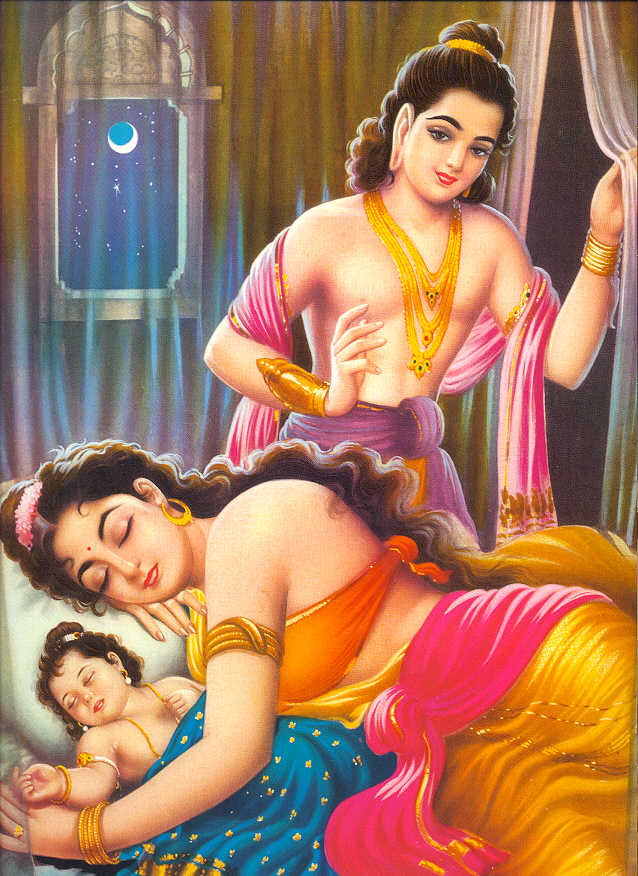

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

I have always been a little uneasy about the part of the Buddha’s life story where he leaves his young wife just as she has given birth, to go off on his own personal “quest.”

But now I’ve just run across this footnote in Turning the Wheel of the Truth: Commentary on the Buddha’s First Teaching, by Ajahn Sucitto:

“Many fables that present the life of the Buddha tell of his marriage and sudden nocturnal departure in a highly dramatic way that was designed to emphasize the great renunciation of the young seeker. Most of us these days would view nocturnal departures as anything but renunciation, so unfortunately this legend has cause the Buddha to be seen more as a jerk than one who negotiated his way out of the jam that his parents had put him in.”

Ah. That does put things is a bit of a different light.

Here’s the text that the footnote refers to:

“…When was he born? Traditions vary, placing his birth date anywhere between 573 B.C.E. and 483 B.C.E. Modern research suggests 480 B.C.E.

“What is more commonly agreed upon is that he was born as the son and heir of Suddhodana, an elected chief of the Sakyan republic. This republic occupied a fragment of southern Nepal on the Indian border, and probably extended into what is now the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The son was named Siddhattha Gotama (Skt.: Siddhartha Gotama).

“Although a lot is made in subsequent legends of his early life, the Buddha only referred to it a few times. The Sakyan republic was not a grand kingdom; it was a vassal state of another small kingdom occupying the northeast of Uttar Pradesh. So he was a nobleman in a small republic.

“In his teens he was bound into an arranged marriage for dynastic reasons. This marriage was anything but a love affair–it’s unlikely that the couple had even laid eyes on each other before the wedding. However that’s the way it was done in those days; the important thing was to bring forth a son as a guarantor for the future of the family. After thirteen years, the couple managed to do that, and so, after some protracted and painful negotiations, Siddharttha got permission from his family to take leave and pursue a spiritual quest as one ‘gone forth.’

“Siddhattha’s departure meant that he gave up everything. He relinquished inheritance, statehood, livelihood, family network, friends, and caste–all the elements that in Indian society gave him a place in the cosmos–which included not only this world and life, but also a future birth.

“So with ‘going forth’ he had put aside his ascribed place in the cosmic order to find a new one for himself. Relinquishment made life starkly simple–a ‘gone forth’ person had to survive on what he or she could glean, and put everything else aside to focus on developing his or her mind, soul, or spirit. Whatever you think of his domestic policy, you can’t fault Siddhartha in terms of putting his life on the line.

“He wasn’t entirely alone in this–there was a whole movement of samanas (religious seekers) doing the same kind of thing–sometimes following a particular teacher and sometimes forming groups and adhering to an ethical code of harmlessness, celibacy, truthfulness, and renunciation.

“To be a true ‘gone-forth one,’ however, the essential factor was to wander free from the ties and comforts of home life. This was life with the veils and wrapping pulled off. It was life among wild animals, thieves, and outlaws–life lived on the hard earth at the roots of trees; seeking alms-food from villages; and looking for something to wear, often pulling rags off the corpses whose jackal-chewed remains littered the charnel grounds.

“It was life held like a brief candle-flame in the vast stormy night of sickness, danger, and death. Only a few ventured into this way fo life, some of dubious sanity, some quiet saintly, but all were held in a mixture of fear and awe by the ordinary folk of town, clan, and family.”