May We All Be Happy

Note: I’ll be entertaining an out-of-town friend starting tomorrow, so I’m taking a little break from posting while she’s here. Check back again on Monday (10/24).

In the mean time, I leave you with the prep work I’ve “assigned” for the Let’s Talk Dharma discussion group that meets at my house tomorrow evening. The topic is Wise Concentration, and the homework is a talk given by Tempel Smith, who spent a lot of time doing metta as a concentration practice and who tells a really great story about the purification process (aka “meltdown”) he went through on a long metta retreat. (The story has a happy ending.)

You can listen to it by clicking here. May you be happy!

***

(That’s me with Tempel and a group of dharma buddies when we were in Burma!)

It Is Not This Constant Thing

On The Current Events

On The Current Events

by Jane Hirshfield

(first published in 1988)

The shadow of countries are changing,

like the figures in the dreams of a long sickness.

Argentina, which used to be so full of sunlight

and heroic, whistling pampas cowboys.

Greece, the lovely heifer of curving horns.

Thailand, Palestine, Salvador.

Of course, it is not this constant thing, history,

but ourselves,

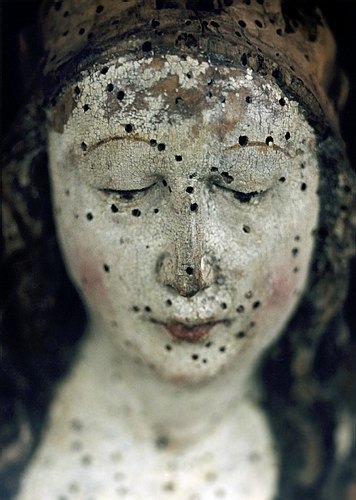

like the wooden statue of some sacred figure,

wormed through,

with the bitter aftertaste on the heart

of too much coffee,

any evening,

after too much talk of unimportant things,

when all of it is important:

the cup placed with such a good fit

on its saucer, well and carefully made,

all the still-pieced pieces of our shared consent.

Until We Reckon

My “Waking Up White” dharma consult group meets again tonight by Skype. It’s one of more than a dozen such groups (made up of white dharma practitioners) that were formed — entirely voluntarily — as an outgrowth of the work the entire (very diverse) Community Dharma Leader group has been doing to recognize — and undo — the systemic racism we’re all a part of, simply as a result of having lived in this country. The CDL program has had a profound effect on the way I understand my place/role in the world — not just the dharma world — and I think the most dramatic effect has come from the study and discussion work I’ve done in this small “Waking Up White” group.

The materials we have been using were originally put together by a group of practitioners (all white) from the East Bay Sangha in Oakland, CA. They include a wide range of books, articles, videos, etc., but the one that really woke me up was written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, titled: The Case for Reparations. (from The Atlantic magazine, 2015)

From the intro: Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.

Reading that article was important. But it was not just reading it that woke me up. It was reading it after also having read and discussed — with a small group of people I felt safe and comfortable with — all the other materials that were provided (beginning with Waking Up White, by Debby Irving) by the East Bay Sangha in Oakland, CA. And it was reading (and discussing) it within a thoughtful set of guidelines and structure.

All of which is now available for use by other peer-facilitated dharma study groups. This is life-changing — world-changing — work. Interested? Email me here.

Be Natural. Be Wise. Be Juicy.

As you can probably tell, I listen to a lot of dharma talks. Sometimes I listen to talks by a lot of different teachers, but mostly I listen to my same old favorites — which is great because I feel like I’m really getting to know them, but also not so great because, frankly, there’s a lot of repetition.

As you can probably tell, I listen to a lot of dharma talks. Sometimes I listen to talks by a lot of different teachers, but mostly I listen to my same old favorites — which is great because I feel like I’m really getting to know them, but also not so great because, frankly, there’s a lot of repetition.

But every so often, even one my “same old favorites” will tell a new story ….usually just when I think I’ve heard every one of their stories, several times over.

Which is what happened when I listened to a talk by Guy Armstrong on The Power of Lovingkindness. The new part was a story about the advice given by a Tibetan teacher at the end of a retreat Guy once attended. It was guidance on taking the teachings back out into the world. The advice was:

1. Be Natural. (Don’t put on “spiritual airs”.)

2. Be Wise. (Be careful with your conduct. Don’t harm people.)

3. Be Juicy. (!!!!)

So, Guy says, the immediate way to manifest the benefits of your practice is to behave in ways that includes the qualities of:

Love

Reverence

Joy

Compassion

Faith

Humility

Devotion

Humor

Awe

Wonder

***

Sounds pretty juicy to me!

Joseph’s “True Confession”

I was listening to one of Joseph’s talks — Creating a Concept of Self — when I was surprised (and delighted) to hear him “confess” to a fondness for mystery novels (a fondness that I share)….and then to hear him close his talk with this passage from a distinctly unusual source of dharma wisdom — the detective novel, Bangkok Tattoo, by John Burnet:

“You see, dear readers, speaking frankly and without any intention to offend, you are a ramshackle collection of coincidences held together by a desperate and irrational clinging.

“There is no center at all. Everything depends on everything else. Your body depends on the environment. Your thoughts depend on whatever junk floats in from the media. Your emotions are largely from the reptilian end of your DNA. Your intellect is a chemical computer that can’t add up a zillionth as fast as a pocket calculator. And even your best side is a superficial piece of social programming that will fall apart just as soon as your spouse leaves with the kids and the money in your joint account, or the economy starts to fail and you get the sack, or you get conscripted into some idiot’s war.

“To name the amorphous morass of self-pity, vanity and despair: “self”, is not only the height of hubris, it is also proof — if any were needed — that we are above all a delusional species. We are in a trance from birth to death. Prick the balloon and what do you get? Emptiness.

“Take two steps in the divine art of Buddhist meditation and you will find yourself on a planet you no longer recognize. Those needs and fears you thought were the very bones of your being turn out to be no more than bugs in your software.”

Much More Listening to Do

Evidence (continued)

by Mary Oliver

3.

I ask you again: if you have not been

enchanted by

this adventure–your life–what would

do for

you?

And, where are you, with your ears

bagged down

as if with packets of sand? Listen. We

all

have much more listening to do. Tear

the sand

away. And listen. The river is singing.

What blackboard could ever be in-

vented that

could hold all the zeros of eternity?

Let me put it this way–if you disdain

the

cobbler may I assume you walk bare-

foot?

Last week I met the so-called deranged

man

who lives in the woods. He was walking

with

great care, so as not to step on any

small,

living thing.

For myself, I have walking in these

woods for

more than forty years, and I am the

only

thing, it seems, that is about to be used

up.

Or, to be less extravagant, will, in the

foreseeable future, be used up.

First, though, I want to step out into

some

fresh morning and look around and

hear myself

crying out: “The house of money is fall-

ing!

The house of money is falling! The

weeds are

rising! The weeds are rising!”

***

(final stanza)

Consider, Always, Every Day

Evidence (continued)

by Mary Oliver

2.

There are many ways to perish, or to

flourish.

How old pain, for example, can stall us

at the

threshold of function.

Memory: a golden bowl, or a basement

without light.

For which reason the nightmare comes

with its

painful story and says: you need to know

this.

Some memories I would give anything

to forget.

Others I would not give up upon the

point of

death, they are the bright hawks of my

life.

Still, friends, consider stone, that is

without

the fret of gravity, and water that is

without

anxiety.

And the pine trees that never forget

their

recipe for renewal.

And the female wood duck who is look-

ing this way

and that way for her children. And the

snapping

turtle who is looking this way and that

way also.

This is the world.

And consider, always, every day, the

determination

of the grass to grow despite the unend-

ing obstacles.

***

(to be continued)

Curious and Full of Detail

1.

Where do I live? If I had no address, as

many people

do not, I could nevertheless say that I

lived in the

same town as the lilies of the field, and

the still

waters.

Spring, and all through the neighbor-

hood now there are

strong men tending flowers.

Beauty without purpose is beauty with-

out virtue. But

all beautiful things, inherently, have

this function–

to excite the viewers toward sublime

thought. Glory

to the world, that good teacher.

Among the swans there is none called

the least, or

the greatest.

I believe in kindness. Also in mischief.

Also in

singing, especially when singing is not

prescribed.

As for the body, it is solid and strong

and curious

and full of detail; it wants to polish it-

self; it

wants to love another body; it is the

only vessel in

the world that can hold, in a mix of

power and

sweetness: words, songs, gesture, pas-

sion, ideas,

ingenuity, devotion, merriment, vanity,

and virtue.

Keep some room in your heart for the

unimaginable.

***

(to be continued)

This Too Needs to Be Heard

As part of the Community Dharma Leader (CDL) program and the awareness to my own cultural blindness it has opened in me, I’ve started reading more books, articles, newspaper stories, etc. about racism and the experience of being black in this country — Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead, for example.

Frankly, it’s been difficult. And painful. And upsetting. But also rewarding.

Then just when I thought I was really being open to the “other,” even congratulating myself on my willingness to listen, to hear the suffering, to see my own contribution to that suffering — I hit the wall at an even more challenging level of habitual “other-ing” in Arlie Hoschschild’s highly acclaimed: Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, subtitled “A Journey to the Heart of Our Political Divide.”

This is one book I really, REALLY did not want to read.

But I know that this too needs to be heard.

So I’ve started in. (Thankfully, the writing is beautiful.)

Here’s a quote from the prelude:

“We, on both sides, wrongly image that empathy with the ‘other’ side brings an end to clearheaded analysis when, in truth, it’s on the other side of that bridge that the most important analysis can begin.

“The English language doesn’t give us many words to describe the feeling of reaching out to someone from another world, and of having that interest welcomed. Something of its own kind, mutual, is created. What a gift.

“Gratitude, awe, appreciation; for me, all those words apply and I don’t know which to use. But I think we need a special word, and should hold a place of honor for it, so as to restore what might be a missing key on the English-speaking world’s cultural piano. Our polarization, and the increasing reality that we simply don’t know each other, makes it too easy to settle for dislike and contempt.”

What it Means to Be Free. Truly Free.

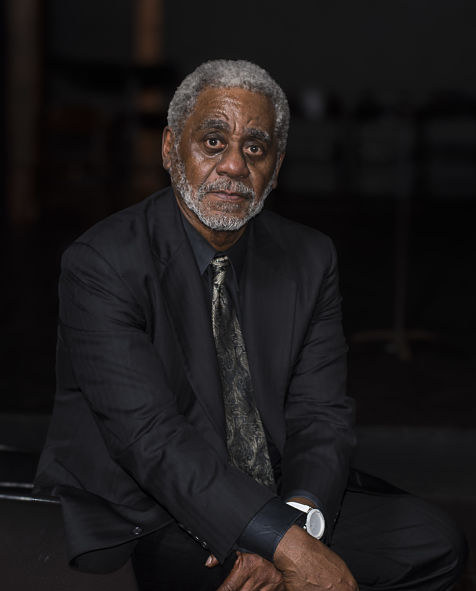

For me as a writer and artist (which I had almost forgotten I was until I heard this man speak about his life — and Buddhism — as an expression of these things), the highlight of the CDL training retreat last week was a visit from Dr. Charles Johnson, the amazing writer, artist, speaker, prize winner, teacher, philosopher….listener!….who I am ashamed to say I had never even heard of before the CDL program.

For me as a writer and artist (which I had almost forgotten I was until I heard this man speak about his life — and Buddhism — as an expression of these things), the highlight of the CDL training retreat last week was a visit from Dr. Charles Johnson, the amazing writer, artist, speaker, prize winner, teacher, philosopher….listener!….who I am ashamed to say I had never even heard of before the CDL program.

To give you just a glimpse of the breath and depth of this man, let me quote from the preface of one of his twenty-two books, Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing.

“From my parents and grandparents, who were born during America’s century of apartheid, from unrecorded stories I heard told by family and friends, then later from a lifetime of studying black culture, literature, and history, I came to see that if black America has a defining essence (eidos) or meaning that runs threadlike from the colonial era through the post-Civil Rights period, it must be the quest for freedom.

“This particular, eidetic sense of our collective meaning, arising out of historical conditions, and the way the Founding Fathers’ ideal of freedom was inscribed with a special meaning in the souls of black folk, has shaped almost every story, essay, novel, drawing, teleplay, and critical article I’ve composed for the last three and a half decades. No matter whether I was writing about Frederick Douglass or James Weldon Johnson, Booker T. Washington or Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ralph Ellison or Phillis Wheatley, my sense of black life in a predominantly white, very Eurocentric society–a slave state until 1863–was that our unique destiny as a people, our duty to our predecessors who sacrificed so much and for so long, and our dreams of a life of dignity and happiness for our children were tied inextricably to a profound and lifelong meditation on what it means to be free. Truly free.

“….The number of black Dharma practitioners will, I predict, grow significantly in the twenty-first century, particularly among our scholars who want a spiritual practice not based on faith or theism and compatible with the findings of modern science; and also among the groundbreaking, innovative artists and writers whose spirit and sense of adventure cannot be contained by the traditions of the West (which, of course, they appreciate), and who hunger–as I did–to experience the world through and be enriched by as many cultural perspectives as possible. All our human inheritance; and all, like Buddhism, have something valuable we can learn.”