How to Stay Woke

Yesterday my CDL “Waking Up to Whiteness” group had a great discussion on Charles Johnson’s novel, Middle Passage, and now we’re moving on to We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Yesterday my CDL “Waking Up to Whiteness” group had a great discussion on Charles Johnson’s novel, Middle Passage, and now we’re moving on to We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

This will not be a comfortable read, but I want to do it because one of the chapters in the book was part of the original “Waking Up to Whiteness” curriculum — and for me, it was THE most memorable of all the readings, and definitely the one that impacted me the most.

It Woke Me Up!

(It was: The Case for Reparations, which you can read here in its original publication in the Atlantic magazine.)

Now with Coates’ new book, I expect the waking up will continue. Here’s a sample:

The central thread of this book is eight articles written during the eight years of the first black presidency–a period of “Good Negro Government”. Obama was elected amid widespread panic and, in his eight years, emerged as a caretaker and measured architect. He established the framework of a national healthcare system from a conservative model. He prevented an economic collapse and neglected to prosecute those largely responsible for that collapse. He ended state-sanctioned torture but continued the generational war in the Middle East. His family–the charming and beautiful wife, the lovely daughters, the dogs–seemed pulled from the Brooks Brothers catalogue. He was not a revolutionary. He steered clear of major scandal, corruption, and bribery. He was deliberate to a fault, saw himself as the keeper of his country’s sacred legacy, and if he was bothered by his country’s sins, he ultimately believed it to be a force for good in the world. In short, Obama, his family, and his administration were a walking advertisement for the ease with which black people could be fully integrated into the unthreatening mainstream of American culture, politics, and myth.

And that was always the problem…

There is a basic assumption in this country, one black people are not immune to, which holds that if blacks comport themselves in a way that accords to middle-class values, if they are polite, educated, and virtuous, then all the fruits of America will be open to them. In the most vulgar terms, this theory of personal Good Negro Government denies the existence of racism and white supremacy as meaningful forces in American life…

But the argument made in much of this book is that Good Negro Government–personal and political–often augments the very white supremacy it seeks to combat.

That is what happened to Thomas Miller and his colleagues in 1895 [after Reconstruction]. That is what happened to black people all through South Carolina during Redemption. It is what happened to black people on the South Side of Chicago during the postwar implementation of the New Deal. And it is what, I contend, is right now happening to the legacy of the country’s first black president.

***

No, this will not be comfortable.

Learning How

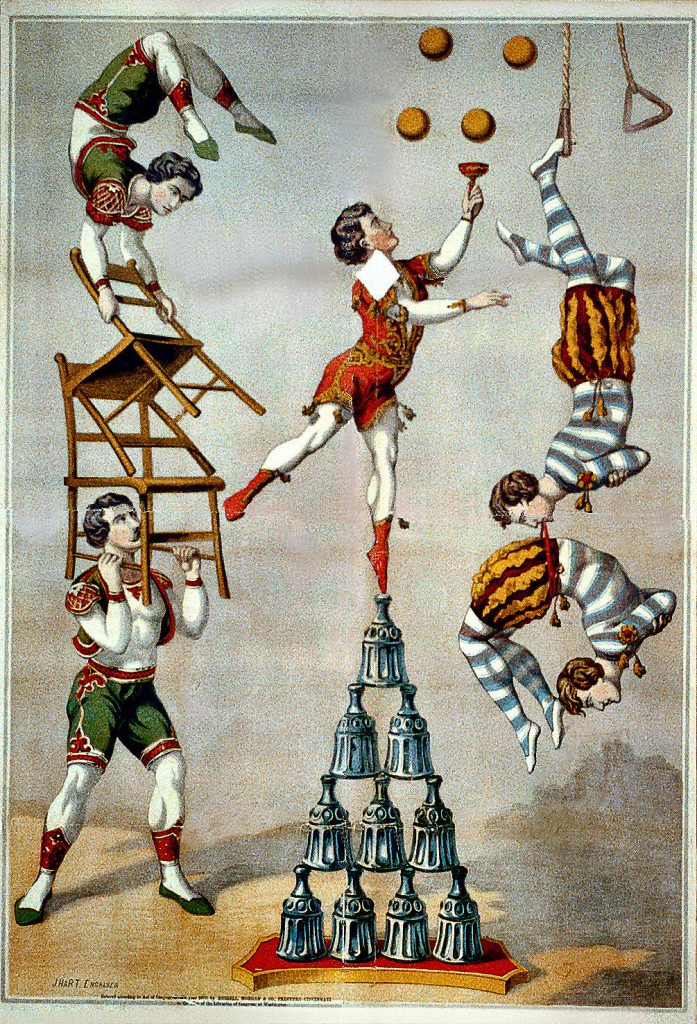

Joining the Circus

Joining the Circus

by Mark Nepo

I just saw a handwritten note from

Galileo. He was under house arrest

for believing we’re not the center of

everything. Now behind me, in the park,

a dozen beginners, of all ages, learning how

to juggle. We have to start somewhere. The

young man who’s so magical at this is asked

to instruct. He smiles, “You have to keep

trying. Just not the same thing.” Earlier,

I leaned over a letter from Lincoln to a

dead soldier’s mother. This, just weeks

after losing Susan’s mother, sweet

Eleanor. I keep saying her name to

strangers. You see, we all have to

juggle joy and sorrow. Not to do it

well–we always drop something–but

when the up and down of life are

leaving one hand and not yet landing

in the other, then we glow, like

a mystical molecule hovering between

birth and death, ready to kiss anything.

Still. And Moving.

As part of getting myself ready for the long retreat I’ll be taking at the end of December (which I posted about here), I’ve been re-listening to talks that were particularly meaningful to me during previous long retreats, especially the talk Phillip Moffitt gave at the end of the March 2016 retreat titled, Awareness: The Still/Flowing Water.

He begins with a teaching from Ajahn Chah, which uses the metaphor of water that is both still and flowing to point to the seemingly paradoxical nature of awareness (not the momentary nature of awareness of a particular object, but the awareness that’s “behind” the awareness of an object — the “knowing that you know” quality of mind that Phillip often talks about.)

He then quotes Ajahn Amaro on the same subject: “The aim of practice is subjectless, objectless awareness. The heart rests in the awareness — the quality of open, spacious knowing. There is the recognition of the mind’s own intrinsic nature: it is empty, lucid, awake, and bright.”

This is quite a profound teaching, which I won’t attempt to paraphrase here. Instead, let me strongly encourage you to listen deeply to this talk.

Consider these questions, which Phillip raises near the end of the talk: “How do we live with the ultimate insult to the ego: that we’re all going to die. That everyone we love will die, and that we too will die. How do we live with that? Where is there a refuge? Where is there a rest for the ego?”

The answer, of course, is what Phillip has been pointing to all along, and which he continues to point to through poetry:

First from Rilke:

I am the rest between two notes,

Which struck together sound discordant

Because death’s note would claim a higher key.

But in the dark pause, trembling,

The notes meet harmonious.

And the song continues,

Sweet.

Then from T.S. Eliot:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered. Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.

I can only say, there we have been; but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

The inner freedom from the practical desire,

The release from action and suffering, release from the inner

And the outer compulsion, yet surrounded

By a grace of sense, a white light still and moving,

Erhebung without motion, concentration

Without elimination…”

***

(erhebung is a German word that means “an ennobling elevation”)

What to Pack for Winter

From December 27 though January 31, I’ll be on a 5-week personal retreat at the Forest Refuge in Barre, Massachusetts. There’ll be experienced teachers on site for guidance during that time (primarily Winnie Nazarko and Annie Nugent), but there won’t be a formal retreat structure, which means no set schedule for practice, no morning instructions, and no nightly dharma talk.

This will be a beautiful way to spend my birthday (Dec 30), New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day, and a full month after that. It will also be an extraordinary chance to develop and strengthen the inner resources I’ve been cultivating as a result of my practice.

So, I’ve been giving a lot of thought to what I want to “take with me” when I go on this retreat. Not how many pairs of underwear and how much dark chocolate I’ll need to get me through the 5 weeks (I’ve pretty much worked all that out on previous retreats), but what else can I bring that will truly sustain and feed me?

I know that what has been the most reliably uplifting for me on previous retreats has been the nightly chanting, especially the chants we’ve done in Pali. I remember being so inspired this past March when Kate Johnson (one of the assistant teachers) chanted the entire Metta Sutta in Pail — by HEART (!!!!).

So now I’ve decided that that is what I want to “pack.”

The Metta Sutta is 10 stanzas long, 4 lines each, and it takes about 4 minutes to chant the whole thing. I already know it in English, but now I want to know it in Pali.

This is no small undertaking.

But I’m doing it.

Because I love it. And because I know this will keep me warm.

***

(Listen here to Jesse Vega-Frey lead this chant during a retreat at IMS.)

The Leaves are Not the Ground

Being Here

by Mark Nepo

Transcending down into

the ground of things is akin

to sweeping the leaves that

cover a path. There will always

be more leaves. And the heart

of the journey, the heart of our

awakening, is to discover for

ourselves that the leaves are not

the ground, and that sweeping

them aside will reveal a path,

and finally, that to fully live,

we must take the path and

keep sweeping it.

In Their Own Quiet Way

I spent last night mesmerized by a gorgeous new book, Wise Trees, by Diane Cook and Len Jenshel, which I think is going to be my Christmas gift to just about everyone on my list this year. Here’s a quote from the introductory essay by Verlyn Klinkenborg:

What trees do in their own quiet way is allow us to think about scale, and they do that better than anything but stars in the night sky.

If you plant a white-oak acorn, you’ll probably think to yourself, “I’ll be dead before this tree is fully grown.” That’s a thought about scale, because a white oak can easily live for three hundred years. With that question comes another: “Will the tree from this acorn ever grow old?”

That could be a question about climate change, but it’s also about patterns of land use and the customs and duration of property ownership. The hills of New England are more heavily wooded now than they’ve been since the late eighteenth century. By 1850, thanks to agriculture and industry, they were nearly as naked as they were when the glaciers receded some 14,000 years ago. That too is a thought about scale.

It’s worth coming at this idea from another direction. To see what I mean, try a thought experiment. Humans have always been framed by trees, from the original savannah onward. As Emerson put it, “They nod to me, and I to them.”

So imagine inhabiting a world where the largest tress are only shoulder hight and live just a single human generation: twenty to twenty-five years, considerably shorter than the average human lifespan. Suppose too that they decompose after death as swiftly as we do. Picture yourself walking among the forests of that strange arboreal world, gazing across the treetops like a giraffe in an apple orchard.

How would it feel? How would it change your conception of who you are? In our world, we’re dwarfed, outlasted, even humbled by trees. What little modesty we have as a species may depend partly on that fact….

Every solitary, ancient tree is by definition a survivor, a sentinel from the past. We tend not to say that what it has survived is us….

What do we say when every ancient tree is a surviver and every standing forest a remnant? One thing that occurs to me is this: if, as a species, we ever learn to withhold ourselves, to think of trees and forests not as survivors but as citizens, then the natural fecundity of Earth would astonish us. I’d like to be an emigrant to a new world on an old planet, where nature at its grandest belongs not only to the past but to the future.

Life Meanders

Brevity

by Mark Nepo

When someone says, “Get to the point,”

I stop talking. It was Mumon in China in

the summer of 1228 who said, “to test real

gold you must see it through fire.” So we

must walk what matters through fire. And

there is no bevity in what we learn from

fire. Or in retrieving what is worth sharing.

Or in what we bring up from the deep like

the pearl diver who painfully tells of the

shell that cut his hand as he scooped the

pearl and how his blood blossomed

underwater like a red net he keeps

dreaming of.

Life meanders to insure we are listen-

ing. Take the birder I met who tells me

of the blackpoll warbler who weighs as

much as a ball point pen, who migrates

every year from Nova Scotia to Venezuela,

pumping its tiny wings for 90 hours without

rest, without food, without touching down,

because the water will cause its wings to sleep

and it will die. The point, to keep winging.

The thrill of the birder makes me go home

and sit very still for a long time till the finch

I know thinks I’m a pole. I open my palm and

wait. It takes forty minutes but she hops into

my hand. I am stunned. She feels like a warm

breeze. I can feel her tiny heart, so fast it stops

my mind. She is soft and uncontainable. My

own heart starts to beat faster. Both of us–

so soft, so necessary, beyond any point.

She flies from my hand as she must–

leaving me bereft of all knowing,

just slightly aglow.

There is Joy There

I listend to another beautiful talk last night, this one by Guy Armstrong. The title is Transcendent Dependent Origination and in it Guy tells a great story about when he was a monk in Burma having a very difficult time. He says that finally, in desperation, he turned to a photo of the Dalai Lama, and asked him for help. Immediately he heard these words (in his head) spoken in the Dalai Lama’s voice:

I listend to another beautiful talk last night, this one by Guy Armstrong. The title is Transcendent Dependent Origination and in it Guy tells a great story about when he was a monk in Burma having a very difficult time. He says that finally, in desperation, he turned to a photo of the Dalai Lama, and asked him for help. Immediately he heard these words (in his head) spoken in the Dalai Lama’s voice:

“Stay cheerful, optimistic and confident. A positive attitude is the best support.”

Then nothing more. Guy felt he had received a transmission from His Holiness, so he really tried to take the message to heart.

“Unfortunately there were times when I couldn’t remember what cheerful felt like,” Guy says, “but when I could, and I could bring that into my mind, it really lifted my spirits and inspired me to go back and practice again.

“This is the role of joy in the practice. When we have a channel to it, a reliable access to it, it becomes a tremendous ally for us when times are difficult.” As an example, Guy talks about the joy of being surrounded by the beauty of nature. “I encourage you to take advantage of that,” he says, “and really open to the beauty. This is not foreign to the path. This is not to antithetical to the path.”

He then quotes Ajahn Sumedho: “Sometimes in Therevada Buddhism one gets the impression that you shouldn’t enjoy beauty. If you see a beautiful flower, you should contemplate its decay. Or if you see a beautiful woman, you should contemplate her as a rotting corpse. That’s a good reflection on anicca (everything is impermanent), dukkha (everything is imperfect), and anatta (everything is impersonal), but it can leave the impression that beauty is only to be reflected on in terms of these three characteristics, rather than in terms of the experience of beauty. This is the joy of mudita: being able to appreciate the joy of beauty in the things around us.”

Guy continues, “So be open to beauty. Let that joy come in and lift us up. It’s intrinsic in the nature of things. When you tune into the way things are, there is joy there.

“I often tune into the way light strikes things. Whether indoors or outdoors, there’s a brightness, there’s a brilliance, there’s a radiance in light that reminds me of that joy and that beauty.”

***

I LOVE that. I’m going to try it!

Ease Into the Conversation

I listened to a great talk last night by Jack Kornfield, given at the Fall Insight Retreat that’s going on right now at Spirit Rock. The title of the talk is Liberation and Mindfulness and in it he touches on the nature of consciousness and liberation in ways that I don’t think I’ve heard from him before.

Of course he does repeat many of his favorite quotes and tells several of his more familiar stories, but he also talks about three levels of mindfulness — Mindfulness of Content, Mindfulness of Process, and Mindfulness of Consciousness — which is definitely different language than I’ve heard him use.

The teachings, of course, are not different. But now Jack seems freer to talk about consciousness — extraordinary states of consciousness, especially — and to speak more directly about the experience of liberation. (Or maybe it’s just that now I’m more able to hear what he’s been saying all along.)

Listen and see for yourself. As Jack quotes at the end of the talk:

Put down the weight of your aloneness and ease into

the conversation. The kettle is singing

even as it pours you a drink, the cooking pots

have left their arrogant aloofness and

seen the good in you at last. All the birds

and creatures of the world are unutterably

themselves. Everything is waiting for you.

— from Everything is Waiting for You, by David Whyte

The “I” That I Was

I’ve just finished reading Charles Johnson’s amazing novel, Middle Passage, and my mind is so blown that I think I might just go back and read it again!

(Who is the “I” that didn’t want to read it? Who is the “I” that’s reading it now?)

Here’s a sample passage (spoken by the narrator after comforting survivors of the devastating mutiny on the slave ship, Republic):

“If you had known me in Makanda or New Orleans, you would have known that I doubted whether I truly had anything of value to offer to others. Obviously, my master thought I did not. Once in Illinois when I felt jealous of Jackson’s chumminess with him and wanted to get on his good side, I asked, ‘Sir, what do you think I can do for others?’ Peering up from under his brow at me, wearing a pair of Ben Franklin wire-frame spectacles, he replied, ‘Yes, that is the question, Rutherford. What can you do?’ It made me feel as if everything of value lay outside me. Beyond. It fueled my urge to steal things others were ‘experiencing.’ Believe me, I was a parasite to the core. I poached watches from Chandler’s bureau and biscuits from his kitchen; I pirated from Jackson’s trousers the change he made selling vegetables from his own garden; I listened to everyone and took notes: I was open, like a hingeless door, to everything.

“And to comfort the weary on the Republic I peered deep into memory and called forth all that had ever given me solace, scraps and rags of language too, for in myself I found nothing I could rightly call Rutherford Calhoun, only pieces and fragments of all the people who had touched me, all the places I had seen, all the homes I had broken into.

“The ‘I’ that I was, was a mosaic of many countries, a patchwork of others and objects stretching backward to perhaps the beginning of time. What I felt, seeing this, was indebtedness. What I felt, plainly, was a transmission to those on deck of all I had pilfered, as though I was but a conduit or window through which my pillage and booty of ‘experience’ passed. And momentarily the injured were calmed, not by the lie — they weren’t naive, you know — but by the urgent belief they heard in my voice, and soon enough I came to desperately believe in it myself, for them I believed we would reach home, and even I was more peaceful as I went wearily back to help Cringle at the helm.”

***

(The image above is a detail from a portrait by Chuck Close. Shrink it — or stand WAY back — and look again.)