I Know What to Do!

In a delightful little collection of essays on Compulsive Helping, Ajahn Amaro writes:

In a delightful little collection of essays on Compulsive Helping, Ajahn Amaro writes:

“Our thinking mind loves to diagnose. I confess to having a thinking mind that loves to figure things out… Certainly the intellect does have its place; it is truly useful to be able to figure out how things work, but we can be over-prone to that.

“We can unwittingly take refuge in having an explanation. The mind can reach forward: ‘I know what’s going on! I understand this. I read a book about it I did a course on this. I know what’s happening here!‘

“We immediately go to the memory, the idea, the concept and in so doing we miss what is before us, what we are in the middle of, what we are a part of. Because we have absorbed our attention in the diagnosis, we miss the actuality.

“I’m not saying that we should never push, make an effort or diagnose. It is not that we should stifle the intellect or suppress our recognition of patterns, rather it’s a question of holding these things in perspective…

“When we’re faced with suffering, particularly other people’s suffering, we can feel: ‘I’ve got to do something!’ Everything is telling us: ‘Don’t just sit there, do something!’… But that urge to help and to do can often be coming from our own insecurity or our own need to be a helpful person. Our need to help may form part of our identity….

“When there is a need to do something, there may indeed be things that we can do, but that very urge, that agitated tension which wants to jump in and fix something, may be the very element that gets in the way….

“I’m not trying to encourage a quality of dissociation… This teaching is not a cold distancing or an attempt to alienate ourselves from feeling the suffering of others. I don’t advocate adopting some kind of false objectivity; I’m not trying to encourage that.

“What I am hopping is that through our spiritual practice we can find that place which is fully empathetic with the suffering of others and the difficulties that we experience, while not suffering on account of them.”

***

This is why Phillip Moffitt alway asks his students to take what he calls “secondary vows of renunciation,” which are: No Judging, No Comparing, No Fixing!

So Many Flavors

Even here in St. Louis, we’ve got a lot of different Buddhist traditions to choose from. (Check out our list at Neighborhood Sitting Groups.)

Is it better to pick just one, or try a few, or to sample them all?

Joseph Goldstein says: “One of the interesting things that’s happening in the transmission of the dharma to the West is that so many different Buddhist traditions are being taught here. People have a wide range of possibilities in terms of how to undertake their practice. It’s a tremendous opportunity to learn from different traditions, but there are also some cautions.

“From my perspective, it’s good to do some initial shopping around—to taste different traditions and see which practice really resonates and inspires us. In some way, that’s the most important thing—that we get enough inspiration from the practice to actually do it.

“But then we need to go into the practice in some depth before we again start to explore other traditions, because otherwise it can get a bit confusing. If it’s based on a solid foundation of understanding, it’s enriching to do some Dzogchen practice, or Zen, or different kinds of Vipassana. That can really expand our dharma view. But if we do it too early, there’s the potential for confusion in the mind. So we have a great opportunity to explore all of the different traditions of Buddhism available to us, but we have to use it judiciously.”

Jack Kornfield says: “Especially when practitioners are starting out, they can latch on to new ideas or beliefs as a way to orient themselves. But Buddhism is not some system or idea or set of beliefs. It is an invitation to have a direct experience of the mystery of your own body and mind. We explore what causes our suffering and what makes us free. We practice skillful means such as mindfulness of the body, loving-kindness, forgiveness, and so forth. These practices are all in the service of liberation, not of creating some new set of ideas or beliefs.

“So if your practice is helping you become more present with the way things are, instead of imposing some view on it, then you will start to feel freer and your practice will deepen.”

***

The above was taken from an interview published in Lions’ Roar magazine. To read more, click here.

Much Easier!

Ajahn Amaro writes: I once met a Wall Street lawyer who had started practicing meditation some half a dozen years previously. She said: “Until I started to meditate it was one conflict after another, and life was one ongoing struggle. But since I began meditating, my relationships have become much more easeful and my working situation is more relaxed, though I’m still working with the same company and I live with the same people.”

Ajahn Amaro writes: I once met a Wall Street lawyer who had started practicing meditation some half a dozen years previously. She said: “Until I started to meditate it was one conflict after another, and life was one ongoing struggle. But since I began meditating, my relationships have become much more easeful and my working situation is more relaxed, though I’m still working with the same company and I live with the same people.”

It was if she thought: “This magical visitation has come into my life and taken all my troubles away!”

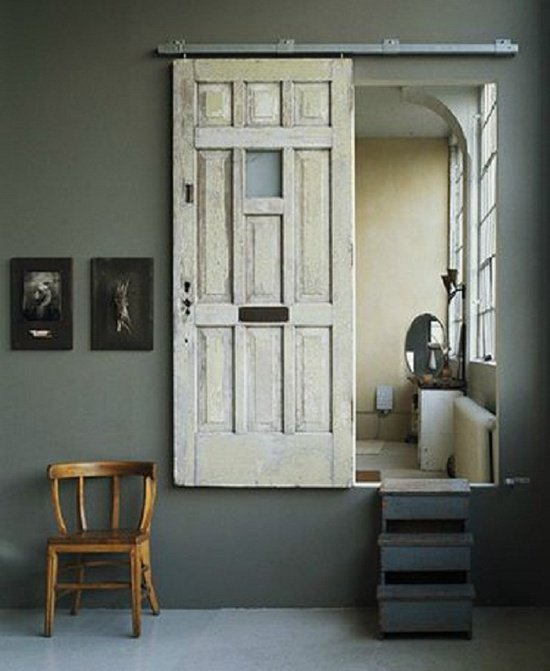

I said: “This isn’t really very magical. It’s more like: you used to get from one room to another by smashing yourself against the wall until you broke through it, and then suddenly you noticed that it’s much easier to go through the doorway. It’s not magic, it’s noticing where the gaps are and aiming for them, rather than just putting your head down and pounding with it until the wall breaks or you fall down unconscious.”

I think she was a little startled, perhaps because she had some internal story about how the devas were helping her and how magical things were.

But often when we apply plain ol’ mindfulness and activate this capacity to be spacious, to see things in context, they open up. Life becomes a lot more easeful and we can find ways to deal with the conflicts, difficulties and apparently intractable situations that we face. We find ways to work with them that surprise us.

It can seem miraculous, but it’s often merely a matter of allowing more spaciousness, a radical acceptance based upon a quality of listening, into the mixture.

Are You Comfortable and Alert?

When I was in Burma a few years ago, I stayed at ShweOoMin monastery and met with the meditation master there, Sayadaw U Tejaniya (pictured), who impressed me in many ways, not the least of which was the deep tenderness I could hear in his voice every morning in the meditation hall. He spoke in Burmese, so I have no idea what he was actually saying, but he seemed to be soothing us — caressing us, even — the way a mother would sooth and caress a small child. (There, there sweetheart. It’s OK. Don’t worry. I’m here.)

When I was in Burma a few years ago, I stayed at ShweOoMin monastery and met with the meditation master there, Sayadaw U Tejaniya (pictured), who impressed me in many ways, not the least of which was the deep tenderness I could hear in his voice every morning in the meditation hall. He spoke in Burmese, so I have no idea what he was actually saying, but he seemed to be soothing us — caressing us, even — the way a mother would sooth and caress a small child. (There, there sweetheart. It’s OK. Don’t worry. I’m here.)

So I was delighted when I saw he has a new book out, titled When Awareness Becomes Natural. I’ve just started reading it and I love it already. I can “hear” the tenderness I remember so well, but also the very direct, down-to-earth instructions he gave, when he spoke in English to our little Spirit Rock group.

Here’s a sample from the book:

“The first instruction I will give a yogi who is new to this practice is to relax and be aware, to not have any expectations or to control the experience, and to not focus, concentrate or penetrate. Instead what I encourage him or her to do is observe, watch, and be aware, or pay attention.

“In this practice it is important to conserve energy, so you can practice continually. If the mind and body are getting tired and tense, then you are putting too much energy into the practice. Check your posture; check the way you are meditating. Are you comfortable and alert?

“You may not have the right attitude. Do you want something out of the practice? If you are looking for a result or want something to happen, you will only tire yourself. It is so important to know whether you are feeling tense or relaxed; check in repeatedly throughout the day; this also applies to daily practice at home or at work.

“If you don’t do this, tension will grow. Whether you are tense or relaxed, observe how you are feeling; observe the reactions. When you are relaxed, it is much easier to be aware; not so much effort is required, and it become an enjoyable, pleasant, and interesting experience.”

***

Check it out for yourself!

I Hereby Pledge Myself

I’ve recently finished reading The Words & Wisdom of Charles Johnson, which I have been savoring since taking it up after Charles Johnson himself met with us as part of the CDL (Community Dharma Leader) program (where I was wowed by his brilliance, his ease, and the dignity of his presence.)

The book is a collection of essays, the last of which is a reflection on the “Commitment Form” that was used during the Civil Rights Movement. Johnson writes:

“…Martin Luther King Jr. said that in the black liberation struggle we always have to work on two fronts, one public and the other private, one external and one internal. One effort is to constantly improve the social world; the other is to constantly improve ourselves. Both efforts are necessary; they reinforce and strengthen each other…

“The men and women of the Civil Rights Movement worked out the Commitment Form, which nicely complements Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of satyagraha, in practice as they moved from one campaign to another in the south. This form(ula), this insight, was fully developed by the time of the electrifying Birmingham campaign in 1963. Men and women, and their children filled the jails of “Bull” Conner in a massive act of civil disobedience. They–and all volunteers–were asked to sign this document, which is as follows:

“Commandments for Volunteers

I hereby pledge myself–my person and body–to the nonviolent movement. Therefore, I will keep the following commandments:

- Meditate daily on the teachings and life of Jesus. [my edit: Meditate daily.]

- Remember always that the non-violent movement seeks justice and reconciliation–not victory.

- Walk and Talk in the manner of love, for God is love.

- Pray daily to be used by God in order that all men might be free. [my edit: Set the intention daily that my efforts be directed to the liberation of all beings.]

- Sacrifice personal wishes in order that all men might be free. [my edit: that all beings might be free.]

- Observe with both friend and foe the ordinary rules of courtesy.

- Seek to perform regular service for others and for the world.

- Refrain from the violence of fist, tongue, or heart.

- Strive to be in good spiritual and bodily health.

- Follow the directions of the movement and of the captain on a demonstration. [my edit: Follow wise counsel.]

“I sign this pledge, having seriously considered what I do and with the determination and will to persevere. Name:_____________________

“…This was not simply a pledge for civil disobedience. This was a grand vision in which the personal and the political were one, a blueprint for how to live… I say all this as a Buddhist who has taken formal vows, the Precepts, as a lay person. (My very Christian wife of 41 years once said that she saw me as being like a Unitarian, someone always looking for the beauty and best in the world’s religions and science, and I guess she was right about that.)…

“Why don’t you, dear reader, print this off right now, and sign it. You’ll feel good, if you do. And M.L.King, wherever he is, will thank you for doing that.”

***

I have printed it off (with my edits) and signed it. And I do feel good! (I also hope M.L.King, wherever he is, will not take offense.)

I Am Not Exempt

My apologies for not posting yesterday, but I was having surgery to remove a spot of skin cancer (not melanoma) that had returned. This was not an especially traumatic event, but it did give me pause.

Maybe that’s why last night I chose to listen to this talk by Joseph Goldstein titled: Deepening Insight into Permanence. It’s an excellent teaching on these 3 reflections:

Whatever is of the nature to grow old, will grow old. I am not exempt.

Whatever is of the nature to fall ill, will fall ill. I am not exempt.

Whatever is of the nature to die, will die. I am not exempt.

So As Not To Miss Out

While I was in Wisconsin helping my parents, several of my dharma friends were sitting the retreat at IMS that Akincano (along with Christina Feldman) taught right before the course on Vedana. So as not to miss out, while I was driving (for 12 hours!) from Wisconsin back to St. Louis, I listen to all the talks from that retreat on Dharmaseed (here).

There was lots of great stuff in those talks. But one tiny little thing (seemingly) that Christina said — almost as an aside — during the final 10 minutes of the last talk of the retreat, has really stuck with me, maybe more than anything else.

She said: “My intention this year — I often have a sort of overriding intention that I use as an investigation — is to have nobody in my life that I’m indifferent towards.

“I find this really startling, in terms of metta. I get on the train or I pass people on the street….or the person at the cash register in the supermarket, the person at the gas station, the people in the hotels who look after us, in the restaurants… It’s so easy to see people in terms of their functions, isn’t it. As if they’re somehow not really worthy of the attention we would give to someone we love, or someone we struggle with. I’ve found this quite a startling practice. Suddenly I seem to live in a much friendlier world!

“This is not about inflicting metta on people. [laugher] It’s not about ‘you’re going to get my metta whether you like it or not. Here it comes!’

“It’s about seeing. It’s about noticing. It’s about what happens in those moments when we offer a glance of tenderness and respect where our gaze falls. Whether we offer an acknowledgment. Whether we offer a smile.

“You know, I have so many subway journeys in London now where I feel like I’m surrounded by friends!“

***

I thought about what she said when I was a Walgreen’s yesterday. The whole place feels really tacky and aggressively “marketing-y” to me, so I tend to avoid eye contact with the cashier when I’m checking out (maybe because I’m embarrassed about shopping there, or embarrassed for them that they have to work there, or guilty maybe because they have to work there and I don’t?!?). But I remembered what Christina said and I looked up and made a point of thanking the cashier (who was really hustling to get me checked out) and it made a huge difference in how I felt. About the experience. About the woman who was working there. About the world, actually. And about myself.

I’m glad I didn’t miss out.

Not Easy

I’m back now from Wisconsin, where I was helping my mother — and my father — adjust to my mother’s deteriorating state of dementia, and from Massachusetts, where I was studying the concept of “feeling tone” in Buddhist psychology — and really getting into the Pali texts!

I’m back now from Wisconsin, where I was helping my mother — and my father — adjust to my mother’s deteriorating state of dementia, and from Massachusetts, where I was studying the concept of “feeling tone” in Buddhist psychology — and really getting into the Pali texts!

I have quite a lot to say about both of these experiences, but for now, let me combine the two by quoting the Buddha (from the Numerical Discourses, AN 2.32):

“I tell you, monks, there are two people who are not easy to repay.

“Which two? Your mother and father. Even if you were to carry your mother on one shoulder and your father on the other shoulder for 100 years, and were to look after them by anointing, massaging, bathing, and rubbing their limbs, and they were to defecate and urinate right there [on your shoulders], you would not in that way pay or repay your parents.

“If you were to establish your mother and father in absolute sovereignty over this great earth, abounding in the seven treasures, you would not in that way pay or repay your parents.

“Why is that? Mother and father do much for their children. They care for them, they nourish them, they introduce them to this world.”

Everything Changes

I’m not sure when I’ll be posting again. Maybe next week. Maybe not.

I’m not sure when I’ll be posting again. Maybe next week. Maybe not.

I’ve just made plans to drive to Wisconsin after the retreat Lila will be leading this weekend because my mom’s dementia has taken a dramatic turn for the worse, and I need to take over from my sister, who’s there with her now, but needs to get back to her job in St. Louis.

It could be that mom is just having a harder time than normal adjusting to the move from St. Louis to Ellison Bay (she and my dad go there every summer). Or it could be something worse. We’ll just have to see.

Whatever it is, it will change. That is for sure.

***

The photo is of my mom that my dad keeps on his desk. I think it’s her high school graduation photo. They got married not long after that. The photo behind the photo is also of my mom, this time holding my little sister, with me looking on. And in the lower corner of that photo, there’s a cut-out from a snapshot of my brother and me, at my college graduation, with my mom in the background looking on.

Everything changes.

Everything.

It Shouldn’t Be, But It Is

I’m not sure why, but I feel drawn today to post this passage from Parami: Ways to Cross Life’s Floods, by Ajahn Sucitto:

I’m not sure why, but I feel drawn today to post this passage from Parami: Ways to Cross Life’s Floods, by Ajahn Sucitto:

“The Buddha famously declared patience to be the supreme purification practice. He was playing on the Vedic term ‘tapas,’ which signifies the taking on of an austerity or ascetic practice such as fasting or mortifying the body in order to cleanse the mind of passions and attachments. But the Buddha pointed not to physical asceticism — which he frequently spoke against — but of the restraint of holding the heart still in the presence of its suffering until it lets go of the ways in which it creates that suffering….

“Patience is not a numbing resignation to the difficulties of life; it doesn’t mean that suffering is all right. It doesn’t mean shrugging things off and not looking to improve our behavior. Nor does it mean putting up with something until it goes away.

“The practice of patience means bearing with dukkah [suffering] without the expectation that it will go away. In its perfection, patience means giving up any kind of deadline, so the mind is serene and equanimous. But if the patience isn’t pure yet (and it takes time to develop patience!), the mind still feels pushy or defensive.

“Impure patience is the attitude: ‘Just hold on and eventually things will get better; I’ll get my own way in the end if I’m patient enough.’ This approach can temporarily block or blunt the edge of suffering, but it doesn’t deal with the resistance or the desire that is suffering’s root.

“Pure patience is the kind of acceptance that acknowledges the presence of something without adding anything to it or covering it up. It is supported by the insight that when one’s mind stops fidgeting, whining and blaming, then suffering can be understood. It is this suffering that stirs up hatred and greed and despair, and it is through practicing the Dhamma, or Way, of liberation that its energy and emotional current can be stopped. Reactivity isn’t the truth of the mind; it’s a conditioned reflex, and it’s not self. Because of that, suffering can be undone, and when it is, the mind is free….

“One year, I decided to not allow my mind to complain about anyone or anything. I was at Amaravati then, which was busy and there was a large community of people of many nationalities, with different languages and from different cultures. So in the general confusion and dysfunction of it all, my longing for simplicity and stability was sorely challenged, and I could get quite irritable. I kept most of it to myself, but still my mind was discontented. Hence the resolution…

“So instead I had to watch the irritation. Just putting up with it didn’t really take me across. I could put up with things and become a patronizing old grump who puts up with things.

“But instead, as the practice of patience deepened, it took me to that point in the mind where I could feel the chafing, the tension, the disappointment — and the wanting to get away from it. At the point, where there was no excuse and no alternative, there was also no condemnation. After all, no one like suffering. And we’re all in this together — wanting peace and harmony, but disappointing and irritating each other nonetheless….

“And from there, my mind began to open into love and compassion for all of us. It shouldn’t be like this, but it is — and we have to support each other. I could realize, ‘There’s nothing wrong with them. They’re my patience teachers, they’re helping me to cross over the flood by getting me to jettison my demands, impatience and narrow-mindedness.’…

“This is the perfection of patience: it can make one’s life a vehicle for blessing.”