Benefit and Happiness

Last night our Book Discussion of Bhikkhu Bodhi’s In the Buddha’s Words focused on chapter IV, which features teachings related to “The Happiness Visible in This Present Life.”

What really caught my attention was this excerpt from the Kutadanta Sutta (one of the teachings of the Buddha):

“…when King Mahavijit was reflecting in private, the thought came to him: ‘I have acquired extensive wealth in human terms, I occupy a wide extent of land which I have conquered. Let me now make a great sacrifice that would be to my benefit and happiness for a long time.’ And calling his chaplain, he told him his thought. ‘I want to make a great sacrifice. Instruct me, venerable sir, how this may be to my lasting benefit and happiness.’

“The chaplain replied: ‘Your Majesty’s country is beset by thieves. It is ravaged; villages and towns are being destroyed; the countryside is infested with brigands. If Your Majesty were to tax this region, that would be the wrong thing to do. Suppose Your Majesty were to think: ‘I will get rid of this plague of robbers by executions and imprisonment, or by confiscation, threats, and banishment,’ the plague would not be properly ended. Those who survived would later harm Your Majesty’s realm.

“‘However, with this plan you can completely eliminate the plague. To those in the kingdom who are engaged in cultivating crops and raising cattle, let Your Majesty distribute grain and fodder; to those in trade, give them capital; to those in government service assigned proper living wages. Then those people, being intent on their own occupations, will not harm the kingdom. Your Majesty’s revenues will be great; the land will be tranquil and not beset by thieves; and the people, with joy in their hearts, playing with their children, will dwell in open houses.‘

“And saying: ‘So be it!,’ the king accepted the chaplain’s advice: he gave grain and fodder to those engaged in cultivating crops and raising cattle, capital to those in trade, proper living wages to those in government service. Then those people, being intent on their own occupations, did not harm the kingdom. The king’s revenues became great; the land was tranquil and not beset by thieves; and the people, with joy in their hearts, playing with their children, dwelled in open houses.”

***

Dear Congress: please take note!

In Defiance of Tragedy

In reference to the wonderful discussion we had in my CDL Waking Up White group this week, I offer this (challenging) excerpt from the book we discussed (and will continue to discuss), Ta-Nehisi Coat’s We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy.

“I don’t ever want to lose sight of how short my time is here. And I don’t ever want to forget that resistance must be its own reward, since resistance, at least within the life span of the resistors, almost always fails. I don’t ever want to forget, even with whatever personal victories I achieve, even the victories we achieve as a people or a nation, that the larger story of America and the world probably does not end well. Our story is a tragedy. I know it sounds odd, but that belief does not depress me. It focuses me. After all, I am an atheist and thus do not believe anything, even a strongly held belief, is destiny. And if tragedy is to be proven wrong, if there really is hope out there, I think it can only be made manifest by remembering the cost of it being proven right. No one–not our fathers, not our police, and not our gods–is coming to save us. The worst really is possible. My aim is to never be caught, as the rappers say, acting like it can’t happen. And my ambition is to write both in defiance of tragedy and in blindness of its possibility, to keep screaming into the waves–just as my ancestors did.”

And When We Have Achieved This…

“White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this–which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never–the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.”

“White people in this country will have quite enough to do in learning how to accept and love themselves and each other, and when they have achieved this–which will not be tomorrow and may very well be never–the Negro problem will no longer exist, for it will no longer be needed.”

— James Baldwin

This Is Possible

Last night our Dharma Book Group had a great discussion about this line from In the Buddha’s Words, by Bhikkhu Bodhi:

“For Early Buddhism, the ideal householder is not merely a devout supporter of the monastic order but a noble person who has attained at least the first of the four stages of realization, the fruition of stream-entry.”

We don’t talk much about stream-entry in our weekly sangha, so I thought it might be helpful to post this explanation of what that is, again by Bhikkhu Bodhi from In the Buddha’s Words:

“The stream-enterer abandons the first three fetters: identity view, that is, the view of a truly existent self either as identical with the five aggregates or as existing in some relation to them; doubt, about the Buddha, the Dhamma, the Sangha, and the trainings; and the wrong grasp of rules and observances, the belief that mere external observances, particularly religions rituals and ascetic practices, can lead to liberation.

“The stream-enterer is assured of attaining full enlightenment in at most seven more existences, which will all take place either in the human realm or the heavenly worlds. The stream-enterer will never undergo an eighth existence and is forever freed from rebirth in the three lower realms–the hells, the realm of afflicted spirits, and the animal realm.”

To which I would like to add these words from the Buddha:

If this were not possible, I would not ask you to do it.

Strong Medicine

Sorry for not posting for almost three weeks, but the night after I took Spring to the airport after her retreat (which was GREAT, by the way) I ended up in the Emergency Room (with what I thought was a detached retina, but which turned out to be nothing serious — thank goodness!) and then right after that I had to catch a train to Kansas City to attend my niece’s (FABULOUS) wedding, and meanwhile there was all the post-retreat business I didn’t get done because I was dealing with all the other stuff, and then my back started seizing up, and then I had pre-Thanksgiving grocery shopping that needed to get done….. And so well anyway, that’s how it’s been.

Sorry for not posting for almost three weeks, but the night after I took Spring to the airport after her retreat (which was GREAT, by the way) I ended up in the Emergency Room (with what I thought was a detached retina, but which turned out to be nothing serious — thank goodness!) and then right after that I had to catch a train to Kansas City to attend my niece’s (FABULOUS) wedding, and meanwhile there was all the post-retreat business I didn’t get done because I was dealing with all the other stuff, and then my back started seizing up, and then I had pre-Thanksgiving grocery shopping that needed to get done….. And so well anyway, that’s how it’s been.

On the plus side however, while I was stretching out my back, I was able to read Spring Washam’s new book, A Fierce Heart: Finding Strength, Courage, and Wisdom in Any Moment. Which I HIGHLY recommend.

But don’t take my word for it. Here’s what Jack Kornfield has to say:

“Amidst uncertain times, we need strong and inspiring medicine. In A Fierce Heart, you will find this medicine: beautiful teachings and heartfelt stories that can transform your day and change your life. The real purpose of these stores is to awaken and empower you. They will remind you of profound possibilities and provide a sweet, healing balm of wisdom and love for your own difficult and joyful journey.

“Told here, Spring’s personal tale is also universal Like the most beloved accounts of sages and shamans, ancient lamas and wise mamas, Spring leads us through the trials and revelations of her own life, to show in intimate and personal ways how the mud we are given can give birth to the lotus…

“In this beautiful book, Spring gives you her all. But remember, this girl from Long Beach who became the shaman from the Amazon, the yogi form the Himalayas, is not here to entertain you. She means to challenge you! To insist that as your read, you reflect and inquire as she has done:

“What is the calling of your own heart?

“How fully are you living your own life, this day, this year?

“How free is your spirit, how wide is your compassion?

“If you were to be more spiritually adventurous, what would that mean?

“Have you considered meditation? Would more if it be good for you?

“How about shamanic practice, or sacred medicine? Do you find a calling to it?

“Are you called to work for justice, to combine it with spiritual courage?

“…Amidst the 10,000 joys and sorrows of your human incarnation, at this time of both miraculous outer development and widespread injustice, all your courage and wisdom and compassion are needed.

“Pause.

“Read this book slowly.

“Let Spring’s stories touch you and enliven you.

“And then, follow their inspiration.

“Let them lead you on your own miraculous journey.

“Many blessings as you go!”

How to Stay Woke

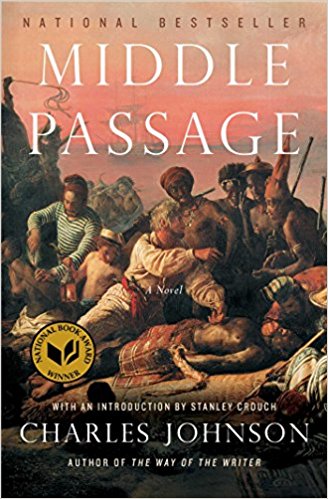

Yesterday my CDL “Waking Up to Whiteness” group had a great discussion on Charles Johnson’s novel, Middle Passage, and now we’re moving on to We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Yesterday my CDL “Waking Up to Whiteness” group had a great discussion on Charles Johnson’s novel, Middle Passage, and now we’re moving on to We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

This will not be a comfortable read, but I want to do it because one of the chapters in the book was part of the original “Waking Up to Whiteness” curriculum — and for me, it was THE most memorable of all the readings, and definitely the one that impacted me the most.

It Woke Me Up!

(It was: The Case for Reparations, which you can read here in its original publication in the Atlantic magazine.)

Now with Coates’ new book, I expect the waking up will continue. Here’s a sample:

The central thread of this book is eight articles written during the eight years of the first black presidency–a period of “Good Negro Government”. Obama was elected amid widespread panic and, in his eight years, emerged as a caretaker and measured architect. He established the framework of a national healthcare system from a conservative model. He prevented an economic collapse and neglected to prosecute those largely responsible for that collapse. He ended state-sanctioned torture but continued the generational war in the Middle East. His family–the charming and beautiful wife, the lovely daughters, the dogs–seemed pulled from the Brooks Brothers catalogue. He was not a revolutionary. He steered clear of major scandal, corruption, and bribery. He was deliberate to a fault, saw himself as the keeper of his country’s sacred legacy, and if he was bothered by his country’s sins, he ultimately believed it to be a force for good in the world. In short, Obama, his family, and his administration were a walking advertisement for the ease with which black people could be fully integrated into the unthreatening mainstream of American culture, politics, and myth.

And that was always the problem…

There is a basic assumption in this country, one black people are not immune to, which holds that if blacks comport themselves in a way that accords to middle-class values, if they are polite, educated, and virtuous, then all the fruits of America will be open to them. In the most vulgar terms, this theory of personal Good Negro Government denies the existence of racism and white supremacy as meaningful forces in American life…

But the argument made in much of this book is that Good Negro Government–personal and political–often augments the very white supremacy it seeks to combat.

That is what happened to Thomas Miller and his colleagues in 1895 [after Reconstruction]. That is what happened to black people all through South Carolina during Redemption. It is what happened to black people on the South Side of Chicago during the postwar implementation of the New Deal. And it is what, I contend, is right now happening to the legacy of the country’s first black president.

***

No, this will not be comfortable.

In Their Own Quiet Way

I spent last night mesmerized by a gorgeous new book, Wise Trees, by Diane Cook and Len Jenshel, which I think is going to be my Christmas gift to just about everyone on my list this year. Here’s a quote from the introductory essay by Verlyn Klinkenborg:

What trees do in their own quiet way is allow us to think about scale, and they do that better than anything but stars in the night sky.

If you plant a white-oak acorn, you’ll probably think to yourself, “I’ll be dead before this tree is fully grown.” That’s a thought about scale, because a white oak can easily live for three hundred years. With that question comes another: “Will the tree from this acorn ever grow old?”

That could be a question about climate change, but it’s also about patterns of land use and the customs and duration of property ownership. The hills of New England are more heavily wooded now than they’ve been since the late eighteenth century. By 1850, thanks to agriculture and industry, they were nearly as naked as they were when the glaciers receded some 14,000 years ago. That too is a thought about scale.

It’s worth coming at this idea from another direction. To see what I mean, try a thought experiment. Humans have always been framed by trees, from the original savannah onward. As Emerson put it, “They nod to me, and I to them.”

So imagine inhabiting a world where the largest tress are only shoulder hight and live just a single human generation: twenty to twenty-five years, considerably shorter than the average human lifespan. Suppose too that they decompose after death as swiftly as we do. Picture yourself walking among the forests of that strange arboreal world, gazing across the treetops like a giraffe in an apple orchard.

How would it feel? How would it change your conception of who you are? In our world, we’re dwarfed, outlasted, even humbled by trees. What little modesty we have as a species may depend partly on that fact….

Every solitary, ancient tree is by definition a survivor, a sentinel from the past. We tend not to say that what it has survived is us….

What do we say when every ancient tree is a surviver and every standing forest a remnant? One thing that occurs to me is this: if, as a species, we ever learn to withhold ourselves, to think of trees and forests not as survivors but as citizens, then the natural fecundity of Earth would astonish us. I’d like to be an emigrant to a new world on an old planet, where nature at its grandest belongs not only to the past but to the future.

The “I” That I Was

I’ve just finished reading Charles Johnson’s amazing novel, Middle Passage, and my mind is so blown that I think I might just go back and read it again!

(Who is the “I” that didn’t want to read it? Who is the “I” that’s reading it now?)

Here’s a sample passage (spoken by the narrator after comforting survivors of the devastating mutiny on the slave ship, Republic):

“If you had known me in Makanda or New Orleans, you would have known that I doubted whether I truly had anything of value to offer to others. Obviously, my master thought I did not. Once in Illinois when I felt jealous of Jackson’s chumminess with him and wanted to get on his good side, I asked, ‘Sir, what do you think I can do for others?’ Peering up from under his brow at me, wearing a pair of Ben Franklin wire-frame spectacles, he replied, ‘Yes, that is the question, Rutherford. What can you do?’ It made me feel as if everything of value lay outside me. Beyond. It fueled my urge to steal things others were ‘experiencing.’ Believe me, I was a parasite to the core. I poached watches from Chandler’s bureau and biscuits from his kitchen; I pirated from Jackson’s trousers the change he made selling vegetables from his own garden; I listened to everyone and took notes: I was open, like a hingeless door, to everything.

“And to comfort the weary on the Republic I peered deep into memory and called forth all that had ever given me solace, scraps and rags of language too, for in myself I found nothing I could rightly call Rutherford Calhoun, only pieces and fragments of all the people who had touched me, all the places I had seen, all the homes I had broken into.

“The ‘I’ that I was, was a mosaic of many countries, a patchwork of others and objects stretching backward to perhaps the beginning of time. What I felt, seeing this, was indebtedness. What I felt, plainly, was a transmission to those on deck of all I had pilfered, as though I was but a conduit or window through which my pillage and booty of ‘experience’ passed. And momentarily the injured were calmed, not by the lie — they weren’t naive, you know — but by the urgent belief they heard in my voice, and soon enough I came to desperately believe in it myself, for them I believed we would reach home, and even I was more peaceful as I went wearily back to help Cringle at the helm.”

***

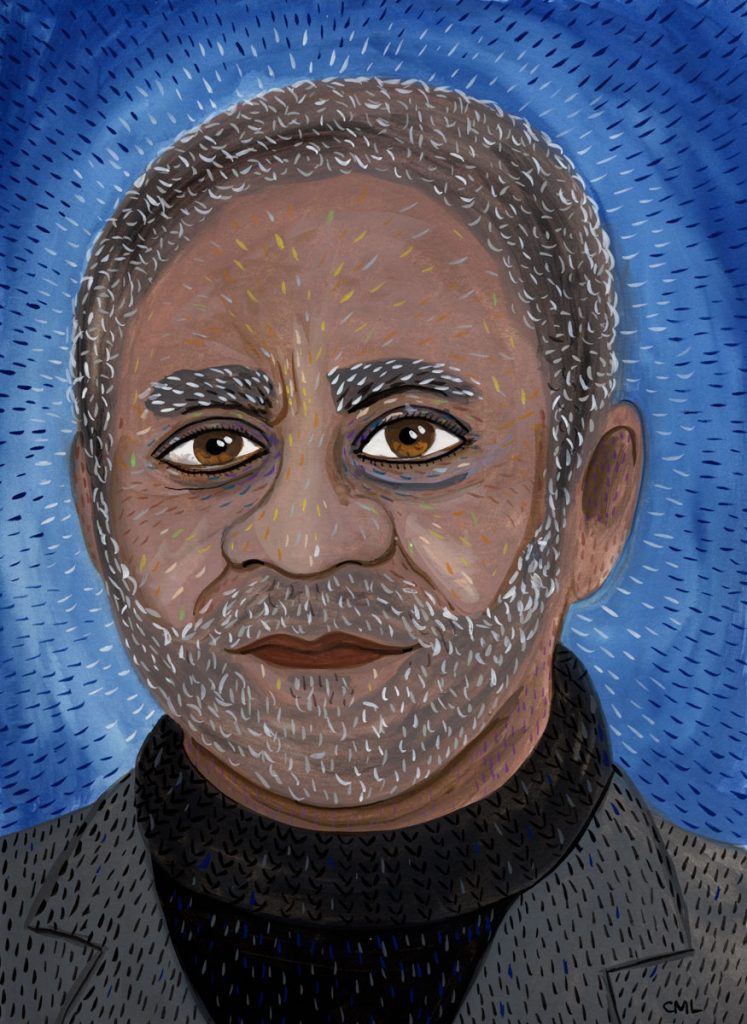

(The image above is a detail from a portrait by Chuck Close. Shrink it — or stand WAY back — and look again.)

All I Can Say is: WOW…

…and: Charles Johnson is a GENIUS. (He did win a MacArthur “Genius” award, after all.)

…and: Charles Johnson is a GENIUS. (He did win a MacArthur “Genius” award, after all.)

So, OK, most of you know that I did NOT want to read his award-winning novel, Middle Passage. (I posted about that here.) The book is about a slave ship and its voyage from Africa to America — and I just did not want to have to deal with that.

But the fact that I was avoiding it was the reason I knew I had to read it.

So I am.

And I am SO glad. Because it is FABULOUS.

Here’s an excerpt:

(The narrator is a freed slave from Illinois, who has moved to New Orleans and become a petty thief.)

How I fell into this life of living off others, of being a social parasite, is a long, sordid story best shortened for those who, like the Greeks, prefer to keep their violence offstage. Naturally, I looked for honest work. But arriving in the city, checking the saloons and Negro bars, I found nothing. So I stole–it came as second nature to me. My master, Reverend Peleg Chandler, had noticed this stickiness of my fingers when I was a child, and a tendency I had to tell preposterous lies for the hell of it; he was convinced I was born to be hanged and did his damnedest to reeducate said fingers in finer pursuits such as good penmanship and playing the grand piano in his parlor. A Biblical scholar, he endlessly preached Old Testament virtues to me, and to this very day I remember his tedious disquisitions on Neoplatonism, the evils of nominalism, the genius of Aquinas, the work of such seers as Jakob Bohme. He’d wanted me to become a Negro preacher, perhaps even a black saint like the South American priest Martin de Porres–or, for that matter, my brother Jackson. Yet, for all that theological background, I have always been drawn by nature to extremes. Since the hour of my manumission–a day of such gloom and depression that I must put off its telling for a while, if you’ll be patient with me–since that day, and what I can only call my brother Jackson’s spineless behavior in the face of freedom, I have never been able to do things halfway, and I hungered–literally hungered–for life in all its shades and hues: I was hooked on sensation, you might say, a lecher for perception and the nerve-knocking thrill, like a shot of opium, of new “experiences.” And so, with the hateful, dull Illinois farm behind me, I drifted about New Orleans those first few months, pilfering food and picking money belts off tourists, but don’t be too quick to pass judgement. I may be from southern Illinois, but I’m not stupid. Cityfolks lived by cheating and crime. Everyone knew this, everyone saw this, everyone talked ethics piously, then took payoffs under the table, tampered with the till, or fattened his purse by duping the poor. Shameless, you say? Perhaps so. But had I not been a thief, I would not have met Isadora and shortly thereafter found myself literally at sea.

***

This is SO great. And SO Buddhist! Stay tuned.

On Choosing

This month, I suggested the novel Middle Passage, by Charles Johnson, for my CDL White Awake group to read. I chose it because although I’ve read almost every book he’s written — and LOVED all of them — I have avoided reading this one.

This month, I suggested the novel Middle Passage, by Charles Johnson, for my CDL White Awake group to read. I chose it because although I’ve read almost every book he’s written — and LOVED all of them — I have avoided reading this one.

Even though it won the National Book Award (1990) and even though it’s his most famous book.

The problem: It’s about SLAVERY. And I’m white. So of course I don’t want to read it.

I’m serious. I really have NOT wanted to read this book. Even though I was mesmerized when he spoke to us at the CDL retreat, and even though he is THE MOST FABULOUS WRITER I’ve come across in a very long time — I have just not been able to get myself to read this book.

But the fact that I haven’t wanted to read it is exactly the reason that I really DO want to read it. Not as some kind of penance. Or because I feel like I “should” read it. Or that it would be “good for me” to read it.

But because I keep feeling drawn to it.

Even as I’m fighting against whatever it is that draws me, I know that there is something in this book that I want. Not something I want to have. Something I want to inhabit.

I’m not exactly sure what I mean by that.

I just know that even though I’m the one who chose this book for us to read — the truth is: this book has chosen me.